A Chicago Story

The History of One of the Most Popular Rock Bands of All Time

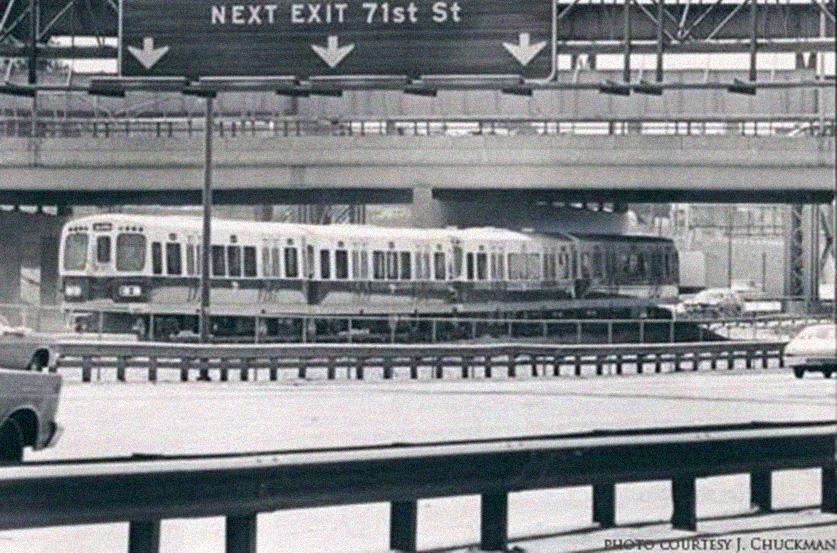

Perhaps more than any other city in the United States, Chicago, located at the center of the nation, has reflected the cultural diversity that has served as both a nurturer of significant musical talent and a magnet that drew the best from other areas. Jazzman Lionel Hampton arrived in Chicago when he was 11 years old in 1919, blues man Muddy Waters got there in 1943, when be was 28. But Benny Goodman, the King of Swing, didn’t have to travel, he was born in Chicago in 1909.

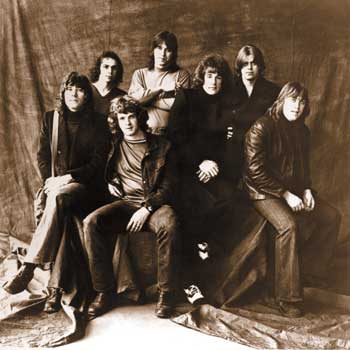

In 1967, Chicago musicians Walter Parazaider, Terry Kath, Danny Seraphine, Lee Loughnane, James Pankow, Robert Lamm, and Peter Cetera formed a group with one dream, to integrate all the musical diversity from their beloved city and weave a new sound, a rock ‘n’ roll band with horns. Their dream turned into record sales topping the 100,000,000 mark, including 21 Top 10 singles, 5 consecutive Number One albums, 11 Number One singles and 5 Gold singles. An incredible 25 of their 34 albums have been certified platinum, and the band has a total of 47 gold and platinum awards.

Chapter I – A Dream

Most pop stars who emerged in the 1960’s will tell you that they got their inspiration by seeing Elvis Presley perform on TV in the ’50’s. But Walter Parazaider, born in Chicago on March 14, 1945, had a slightly different experience. “I started playing when I was nine years old because I saw Benny Goodman on The Ed Sullivan Show,” he says. “I was a clarinetist to start with.” Parazaider came by his interest in music naturally. His father was a musician who had turned from full-time to part-time work when he started a family. “I can’t think of a time growing up when there wasn’t music in the house,” Parazaider says, “whether it was my dad practicing by himself or playing in a band that was rehearsing at the house, or my mother listening to records, and that’s from my earliest recollection.” As a result, when he began to take an interest in playing music himself, “the support that I had from my mother and father over the years was phenomenal.” Parazaider studied and practiced the clarinet for the next several years, and by his teens had displayed so much proficiency that he became the protege of Jerome Stowell, who was the E-flat clarinetist in the Chicago symphony.

But even for a classical music prodigy, the late ’50’s were a time when other forms of music exerted an influence. “I picked up the saxophone along the way,” Parazaider recalls, “and discovered that you could make a buck and get some girls playing a saxophone in a rock ‘n roll band. So, I enjoyed a schizoid musical existence, so to speak, from about the age of 13 on, playing in anything from an octet playing all the standard big band tunes, any rock ‘n’ roll from Tequila to any of the Ventures stuff that they’d use a saxophone on, and did that along with pursuing the classical career, because my idea at that time was to take my teachers place in the Chicago symphony.”

But even for a classical music prodigy, the late ’50’s were a time when other forms of music exerted an influence. “I picked up the saxophone along the way,” Parazaider recalls, “and discovered that you could make a buck and get some girls playing a saxophone in a rock ‘n roll band. So, I enjoyed a schizoid musical existence, so to speak, from about the age of 13 on, playing in anything from an octet playing all the standard big band tunes, any rock ‘n’ roll from Tequila to any of the Ventures stuff that they’d use a saxophone on, and did that along with pursuing the classical career, because my idea at that time was to take my teachers place in the Chicago symphony.”

Pursuant to that goal, Parazaider enrolled at Chicago’s DePaul University, where his teacher, Hobie Grimes, taught, all the while still playing “Many gigs and smoke-filled rooms and dance halls, and also some orchestra balls.” It was at DePaul that he met another young Chicago musician, Jimmy Guercio, who years later would become Chicago’s producer. “We started playing in different rock ‘n’ roll bands in the area,” Parazaider recalls, “played a lot of the beer bashes at Northwestern University and the surrounding colleges in the area, and we became quite friendly.” Meanwhile, Parazaider was maintaining his “schizoid” musical existence at DePaul, though with increasing difficulty. He recalls, “After about a year and a half of realizing I didn’t want to study trigonometry and how to teach health class in school, and also realizing with the help of some of my professors that, because I wasn’t a patient person, I wasn’t cut out to be a teacher. I changed my major. I prepared for about a year and a half and played a degree recital for the principal members of the Chicago symphony and an audience. I passed with flying colors and received a playing degree in orchestral clarinet. In the meantime, I had taken all my masters credits in English Lit.”

But while doing all that academia work, Parazaider had also gotten a non-classical musical idea he thought had promise: a rock ‘n’ roll band with horns. In the trendy world of pop music, horns took a back seat in the mid-’60’s, when bands, imitating the four-piece rhythm section of the Beatles, stayed with the limits of guitars-bass-drums. Even the Saxophone, so much a part of ’50’s rock ‘n’ roll, was heard less often. Only in R&B, which maintained something of the big band tradition, did people such as James Brown and others continue to use horn sections regularly.

In the summer of l966, the Beatles turned around and brought horns back. Their Revolver album featured songs such as “Got To Get You Into My Life,” which included two trumpets and two tenor saxophones.

Chapter II – The Birth of a Band

Parazaider’s current band at the time was the Missing Links, which featured a very talented guy named Terry Kath on bass. Kath, born in Chicago on January 31, 1946, had been a friend of Parazaider’s and Guercio’s since they were teenagers. On drums was Danny Seraphine, born in Chicago on August 28, l948 , who had been raised in Chicago’s Little Italy section. Trumpet player Lee Loughnane, another DePaul student, sometimes sat in with the band.

Parazaider’s current band at the time was the Missing Links, which featured a very talented guy named Terry Kath on bass. Kath, born in Chicago on January 31, 1946, had been a friend of Parazaider’s and Guercio’s since they were teenagers. On drums was Danny Seraphine, born in Chicago on August 28, l948 , who had been raised in Chicago’s Little Italy section. Trumpet player Lee Loughnane, another DePaul student, sometimes sat in with the band.

Loughnane, born in Chicago on October 21, 1946, was the son of a former trumpet player. “My dad was a product of the Swing Era,” he recalls. “He was a bandleader in the Army Air Force in World War II.” In that capacity, Chief Warrant Officer Loughnane worked with some of the top players from the big bands of the era, who had been drafted. But he also came in contact with their lifestyles. “My dad knew that they were only going to be with him for a certain amount of time, and then they were going to get shipped out to the front lines,” says Loughnane. “So, he was a little more lax in his discipline than he might have been under other circumstances. Some of the guys would go AWOL on weekends to play gigs in town and then come back drunk or high on something, and my dad would cover for them. As a result, he gained a dislike for drugs and alcohol, and when he left the army, he left the music behind. The only thing he brought home was his trumpet, which was the first one that I used. I had never heard him play.”

Loughnane began trying to play that trumpet at the age of 11. When he was 11, in the summer of 1959, between seventh and eighth grades, he met with the band director, Ralph Meltzer. “He wanted me to show him my teeth,” Loughnane recalls. “If you have any crooked teeth, you start messing up your lip because of the pressure. My teeth were okay. He gave me some “Mary Had A Little Lamb” books, and I couldn’t wait to go home and play the songs. My dad then found me a private teacher by the name of John Nuzzo. He started giving me some lessons, and my playing improved immensely.”

When Loughnane went to high school, be enrolled at St. Mel’s High School rather than St. Patrick’s, which was much closer to his home, because St. Mel’s had a concert band, a jazz band, and a marching band. Also, the band director, Tom Fabish, had taught Loughnane’s father when he was in high school. “Tom was a major influence on my playing, and he and my dad wanted me to go to a school where l could play music,” he says. “I didn’t like the marching part of it too much, however. They could never get me to lift any legs up and look good as a marcher. ‘You want to hear the parts or you want me to march?’ I was always into making the music sound good, and that still lives within my thinking on-stage. But now I have learned how to be more of a performer and still play as good as I can rather than trying to jump around and miss a lot of notes. I’ve always thought it was very important to be true to the music.”

By the time he graduated from high school in 1964, Loughnane knew that he wanted to be a professional musician. “There was nothing else that I wanted to do,” he recalls. “I had no other calling.”

“Tom Fabish was also the band director at DePaul University, so when I got ready to enroll in college, it was the perfect school. Tom, my dad, and I decided that if I was intent upon a career in music, I should get a teaching degree for insurance, just in case my lofty plans at success as a professional musician didn’t pan out.” But, as with Parazaider, it didn’t work out that way. “I loved the music classes, but I didn’t so much love the general education classes that I had to take in order to get that kind of degree,” Loughnane says, “and I would get to the point where I just wouldn’t go to those classes.”

Maybe that was because his extracurricular activities were taking up so much of his time. Like other future members of Chicago, Loughnane began performing in local groups. First, there was the Shannon Show Band, an Irish group in which he found himself part of a three-man horn section trumpet, trombone, and tenor saxophone just like the one Chicago would use. Catering to the large Irish population of the city, the Shannon Show Band appeared at such venues as the Blarney Club, playing Elvis Presley, country and western, and Top 40 music, in addition to the obligatory Irish waltzes. “I even sang my first lead vocal in that band,” Loughnane recalls. “I sang “Kicks,” by Paul Revere and the Raiders. I was so good at it that I became a singing sensation with Chicago. I sang three leads on 23 albums!”

Loughnane’s other band in this period was Ross and the Majestics, who earned a residency one summer in a bar in the basement of the Palmer House, a ritzy Chicago hotel. To take the gig, Loughnane was forced to leave a summer job his father had arranged for him on the graveyard shift at Revere Copper and Brass Company. “Dad and I disagreed on my decision to take the job with Ross, but that was the band at the time, and I couldn’t let them down.”

Another summer job at the Chicago State Hospital only confirmed Loughnane’s dislike of manual labor. “I knew that playing the trumpet was a lot more fun and definitely easier on the back,” he says. Later that summer, be decided it was time to spread his wings. “I went out and got an apartment, and then I met Terry.”

Through Kath, Loughnane met Seraphine and Parazaider, and he started to sit in with the Missing Links. Terry and I became thick as thieves,” he recalls. “Walt was the only horn player in that band, and he encouraged me to come by and sit in a lot so there would be two horns and you could get that octave R&B sound. It was sort of the thing at the time, and I really enjoyed playing with the band.”

Now, Parazaider, Kath, Seraphine, and Loughnane decided to develop Parazaider’s concept for a rock ‘n roll band with horns. To make the concept work, they needed to bring in additional band members. The first musician Parazaider approached, in the fall of 1966, was a newly transferred DePaul sophomore from Quincy College who played trombone. “Walt had been kind of keeping an eye on me in school,” says James Pankow. “He approached me and said, “Hey, man, I’ve been checking you out, and I like your playing, and I think you got it. I said, “Well, what do you mean, I got it?” He had that twinkle in his eye, and I figured, well, whatever the hell be means, I guess he likes what I do.”

Pankow, born in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 20, 1947, had certainly spent enough time with his instrument by then to have gotten something. “I was in fifth grade, and my folks realized that I was a human beat box,” he says. “I was kicking to records in the crib before I could walk, and I was snapping my fingers and tapping on walls and making all kinds of gestures in tempo with whatever music they were listening to. They figured they better channel this nervous energy, so they took me to an audition at the local elementary school, and I of course wanted to play drums or guitar or sax. Nobody wanted to play trombone. It wasn’t cool.”

But a conference took place between Pankow’s parents and the band director (who happened to be a trombone player), and, as Pankow notes, “might makes right, and between my parents and the band director, they persuaded me to try something that was less competitive. So, bottom line, I wound up with the trombone, and for the first three years it was sheer hell.”

One reason for this was the difficulty for a ten year-old in maneuvering such a large instrument. “It was like putting a dwarf in a semi and telling him to drive to New York,” says Pankow. But by his mid-teens, with the encouragement of a father with an enormous record collection who took him out to local nightspots, Pankow began to enjoy the horn, so much so that he even persevered with it during three bruised and bloody years spent with braces on his teeth.

Pankow’s musical aspirations were encouraged at Notre Dame High School by Father George Wiskirchen, who, he remembers, “wrote the book on high school jazz lab and big bands,” and who took the young trombone player under his wing. “I played in concert band and marching band,” Pankow says, “but the high school jazz band was my saving grace and my real love.”

After high school, Pankow won a full music scholarship to Quincy College, but like Parazaider and Loughnane, he was starting to be tempted from his studies by the fun he could have and the money he could earn in bar bands. After his freshman year, he went home for summer vacation and put a band together that got work doing society parties, colleges, weddings, and bar mitzvahs. He also acquired an agent who got him pickup gigs with all the big bands coming through Chicago. As fall approached, Pankow had become so involved with his work that he did not want to give it up. He telephoned his teacher at Quincy to say he was not returning for the fall semester. But be intended to continue his education, and so enrolled at DePaul.

Pankow’s recruitment brought the new band’s complement of horns up to three, but they still needed bass and keyboards. They thought they had found both in a dive on the South Side when they heard piano player “Bobby Charles” of Bobby Charles and the Wanderers, whose real name was Robert Lamm.

Lamm, born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 13, 1944, like Pankow seemed to be rocking in the cradle. “I was interested in music from the time I was a toddler,” he says. “Both my mother and father were collectors of jazz records, and there always seemed to be music playing at our house.”

Lamm’s first formal music training came when his mother put him in a Brooklyn Heights choir. It was here that he began playing the piano and found that be could sit down and pick out songs by ear.

When Lamm was 15, his mother remarried and moved the family to Chicago, where he met other aspiring high school musicians and they put a band together. He also studied with the prominent jazz teacher Millie Collins. His idol became Ray Charles, who both wrote and played, and Lamm named himself after his hero. “I was writing songs in a band or two before Chicago,” he recalls, “the dubious quality of which is another discussion. Writing songs wasn’t yet the all-consuming passion it is now.”

Lamm received a phone call. He isn’t sure who called him, but the voice on the other end of the phone outlined the ideas of forming a band that could play rock ‘n roll with horns in it and asked it he was interested. He said he was. He was also asked if he knew how to play the bass pedals on an organ, thus filling up another sound in the band. “I lied and told them I could,” he says. “I needed to learn how to do it real quick, and I did, on the job.”

Lamm met the rest of the guys at a meeting set up to determine how to go about achieving their musical goals. The date was February 15, 1967. “We had a get together in Walter’s apartment on the north side of Chicago,” says Pankow. “It was Danny, Terry, Robert, Walter, Lee, and myself, and we agreed to devote our lives and our energies to making this project work.”

They rehearsed in Parazaider’s parents’ basement as often as they could. “We figured that the only people with horn sections that were really making any noise were the soul acts,” says Pankow, “so we kind of became a soul band doing James Brown and Wilson Pickett stuff.”

The group needed a name. Parazaider recalls: “An Italian friend of mine who was going to book us said, “You know, everybody is saying “Thing, Thing this, Thing that. There’s a lot of you. We’ll call you the Big Thing.”

Chapter III – The Big Thing

The Big Thing played its first engagement at the GiGi A-Go-Go in Lyons, Illinois, in March 1967. In June, July, and August, the band appeared in Peoria, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Rockford, and Indianapolis. But the most important early gig was a week-long stand at Shula’s Club in Niles, Michigan, from August 29 to September 3.

The Big Thing played its first engagement at the GiGi A-Go-Go in Lyons, Illinois, in March 1967. In June, July, and August, the band appeared in Peoria, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Rockford, and Indianapolis. But the most important early gig was a week-long stand at Shula’s Club in Niles, Michigan, from August 29 to September 3.

In Niles, they arranged a meeting with Parazaider’s old friend Jimmy Guercio, who had become a producer for CBS Records. “He heard us play,” Parazaider recalls “He was very impressed.” It was the big break they had been looking for. Guercio told the band to hang on, that he would be in touch. Encouraged by this, they began to develop more of their own original material. “I began to write songs,” says Pankow. “Robert began to write more songs, and Terry Kath began to contribute material.”

Meanwhile, the Big Thing stayed on the Midwest club circuit through the fall, building a following. An engagement during the second week of December proved to be another important gig. “We were an opening act at Barnaby’s in Chicago for a band called the Exceptions, which was the biggest club band in the Midwest, and we stuck around and listened to them,” says Pankow. “I was just blown away.”

If the Big Thing had stayed late to see the Exceptions, one of the Exceptions had come early to see the Big Thing. “I had heard a lot about these guys,” says Peter Cetera, then the bass player for the Exceptions. “I was just floored ’cause they were doing songs that nobody else was doing, and in different ways. They were doing the Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour” and “Got To Get You Into My Life” and different versions of rock songs with horns.” After the gig, says Pankow, he approached us and said, “I don’t know what you guys are doing, but I like it. It’s really refreshing. It’s cool.” “At the end of the two-week stint, ” says Cetera, “I was out of the Exceptions and into the Big Thing.”

Peter Cetera was born in Chicago on September 13, 1944, and his first instrument was the accordion, which he took up then he was ten. “That’s unfortunately true,” he admits, when asked about it. “There was accordion and guitar, and for some reason I chose accordion. I don’t know why. I guess because I was half Polish, and we played a lot of polkas. It didn’t do me any good for my rock ‘n’ roll career, but it actually was a lot of fun.”

His more serious musical career commenced a little later. “I started listening to music,” he recalls, “and when I was a sophomore in high school, I bought a little guitar from Sears and started singing at the school functions. I met a senior who played guitar, and we started singing together.” He said, “Let’s start a group,” and I went, “Fine, I’ll buy a bass.” We played all the Homecoming dances and all the weekend dances, doing Top 40 material. My senior year, I got together with the Exceptions. I stuck with them for five or six years.”

Cetera perfectly fit the musical needs of the Big Thing. “We needed a bass player at the time,” notes Loughnane. “Robert was playing the bass pedals on the organ. He did a pretty good job, but there just wasn’t enough bottom with the bass pedals. You needed a real bass in the band. And we needed a tenor voice. We had two baritones (Lamm and Kath), so we had midrange and lower notes covered. But we needed a high voice for the same reason that you have three horns. You have trumpet, tenors and trombone. You cover as much range harmonically as you can, and we wanted to do the same thing vocally. When Peter joined the band, that solidified our vocals. You could get more color, musically, and we started building from there.”

It was probably at the Big Thing’s next appearance at Barnaby’s, March 6 – 10, l968, that Guercio came back for a second look. Impressed by the band’s improvement, he took action. “He told us to prepare for a move to L.A.,” says Pankow, “to keep working on our original material, and he would call us when he was ready for us.”

Chapter IV – Chicago Transit Authority

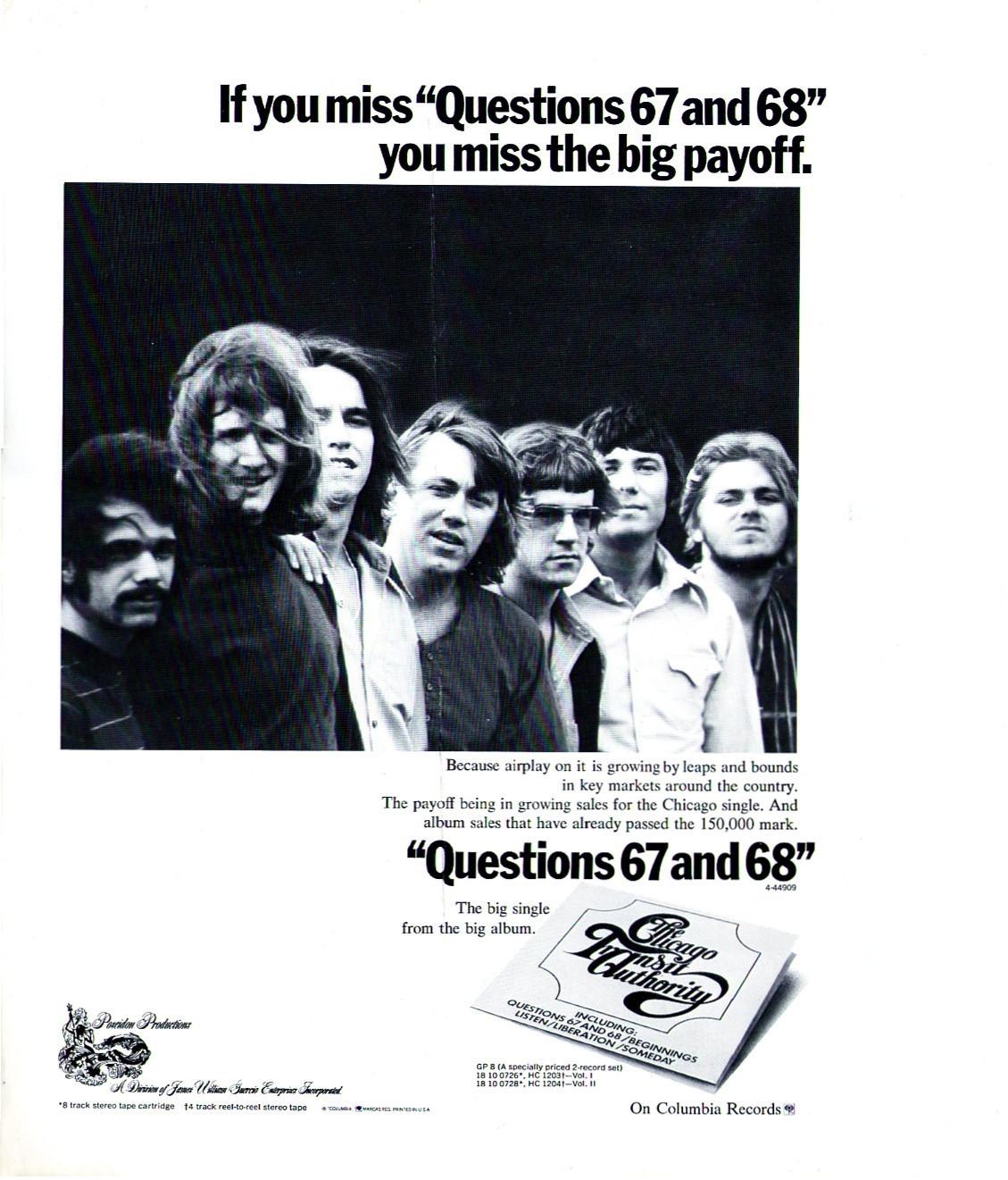

The band, now renamed Chicago Transit Authority by Guercio in honor of the bus line he used to ride to school, was in a creative fervor. Kath, Pankow, and especially Lamm were writing large amounts of original material, with Lamm completing two of the group’s most memorable songs, “Questions 67 and 68” and “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” just prior to the departure from Chicago.

Guercio moved quickly. “He got a little two-bedroom house near the Hollywood Freeway, and he told us that he was ready,” Pankow recalls. “We made the move in June of 1968. We threw all of our lives in U-haul trailers and drove across the country. The married guys left their wives at home at first because they couldn’t afford to bring their families out. We got disturbance calls from the neighbors five times a day because all we did was practice day and night.”

The band began to play around the Los Angeles area. “I think we made all of $15, $20 at whatever beer hall we could play in the suburbs of Los Angeles for a while there,” says Parazaider.

But in addition to the money, they were earning new fans, one of whom was Tris Imboden, a 16 year-old surfer and aspiring drummer. “I remember going to the Shrine Auditorium,” he says. “I had gone to see Procol Harum, and Arthur Lee and Love were playing, too. I walked in, and on another stage was this band with horns, and, man, it just stopped me cold in my tracks. I just went, “Good God! This is the best thing I’ve ever heard,” because it was a blend of so many things that I loved, R&B and jazz and rock ‘n roll, and the vocals were so strong, between Robert and Terry and of course Peter. Danny Seraphine was just on fire that night, too, so he really grabbed my attention. I was asking everybody, “Who is this?” and it’s CTA, Chicago Transit Authority. If somebody had told me, “Tris, one day you’re going to be the drummer of that band,” I would have said, “Yeah, right. And I’m Napoleon.” I wouldn’t have believed it.” It would take 22 years, but eventually, Tris Imboden did become Chicago’s drummer.

But in addition to the money, they were earning new fans, one of whom was Tris Imboden, a 16 year-old surfer and aspiring drummer. “I remember going to the Shrine Auditorium,” he says. “I had gone to see Procol Harum, and Arthur Lee and Love were playing, too. I walked in, and on another stage was this band with horns, and, man, it just stopped me cold in my tracks. I just went, “Good God! This is the best thing I’ve ever heard,” because it was a blend of so many things that I loved, R&B and jazz and rock ‘n roll, and the vocals were so strong, between Robert and Terry and of course Peter. Danny Seraphine was just on fire that night, too, so he really grabbed my attention. I was asking everybody, “Who is this?” and it’s CTA, Chicago Transit Authority. If somebody had told me, “Tris, one day you’re going to be the drummer of that band,” I would have said, “Yeah, right. And I’m Napoleon.” I wouldn’t have believed it.” It would take 22 years, but eventually, Tris Imboden did become Chicago’s drummer.

According to the terms of his production deal with CBS, Guercio was given the opportunity to showcase prospective signings for the label three times. He arranged Chicago Transit Authority’s first showcase at the Whisky-A-Go-Go in August, but CBS’s West coast division turned them down. A month later, CBS turned CTA down again, strike two.

Running short of money, Guercio was asked to produce the second album by Blood, Sweat & Tears, a jazz-rock group on CBS. Intending to use his earnings from the project to continue funding Chicago Transit Authority and to find a way to get them signed to CBS, Guercio sought the band’s permission to produce someone else.

“Jimmy called me up, and be asked me to ask the other guys, would it be okay if he did the Blood, Sweat & Tears second album,” Parazaider recalls. “At first I was going, Well, jeez, man, that’s horns, and what’s going on?” and I voiced that opinion to him. He says, “To tell you the truth, I really haven’t recorded horns as a whole band situation. I’ve recorded horns that did sort of blaps here and there or little parts here and there. This would be a good way for me to learn how to record horns.” I don’t think it was lip service, because he really hadn’t recorded horns per se. We were basically a band with integrated horns in the band, not as backup horns. I had to believe him on this because, if you think about it, what the horn section did, from the start, was a lot different from Blood, Sweat & Tears, and the sound was copied many times over after we got the Chicago horn sound.” So, I think with Blood, Sweat & Tears the horns were recorded in a much different way than Chicago’s horns were. Of course, if you look at the two bands, you would say that they were really a jazz-rock ‘n’ roll band, where we were different. They called us a jazz-rock band after Blood, Sweat and Tears faded away, but we were basically a rock ‘n’ roll band with horns.”

Instead of risking another showcase with CBS, Guercio cut a demo of CTA, and when it began to get notice in the industry, CBS president Clive Davis reversed the decision of the West Coast executives and signed the group.

Seven months after arriving in California, almost two years since they had come together in Parazaider’s apartment, and after more than a cumulative half century of playing and practicing, the seven members of Chicago Transit Authority finally were given a chance to show the world what they could do.

Chapter V – Making a Statement

In January 1969, when the group flew to New York to begin work on its first album, it faced two problems it knew nothing about. The first was that, because the Guercio-produced Blood, Sweat and Tears LP at first appeared to be a flop (though it later became a spectacular hit), the status of his new project, CTA, suffered: The label curtailed the amount of time the band would have in the CBS studio. The group was allowed only five days of basic tracking and five days of overdubbing. And then there was the second problem. Although they were well rehearsed, the band members had never been in a studio before.

“We actually went in and started making Chicago Transit Authority and found out we knew very little about what we were doing,” says Walt Parazaider. “I had done commercial jingles in Chicago, but this was a totally different thing for all of us. The first song was “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” We tried to record it as a band, live, all of us in the studio at once. How the hell do you get seven guys playing it right the first time? I just remember standing in the middle of that room. I didn’t want to look at anybody else for fear I’d throw them off and myself, too. That’s how crazy it got. I think that we actually realized after we didn’t get anything going that it had to be rhythm section first, then the horns, and that’s basically how we recorded a lot of the albums.”

But after they worked out the basic mechanics of recording, the large bulk of material the band had amassed began to be a problem to fit on the then standard 35-minute, one-disc LP. The band had more than enough material for a double album, and they wanted to make a statement.

If they had lot to say, this seemed like the time to say it. Early 1969 was a period when rock was taking on a seriousness undreamed of only a few years before. The Beatles had recently released their two-record “white” album and had also shattered the previously sacrosanct three-minute limit for a single by spending over seven minutes singing “Hey Jude.”

When told of the band’s intention to make a double album, Columbia’s business people informed Guercio that CTA could have a double album only if they agreed to cut their royalties. The band agreed.

Chicago Transit Authority is a time capsule of the popular musical styles of the late ’60’s, with CTA’s own unique flavor on top. One can pick out the group’s classical, jazz, R&B, and pop influences, bearing references to Beatles as well as Jimi Hendrix. One can hear the band’s own history: Kath’s “Introduction,” which does in fact introduce the band in confessional form (“We’re a little nervous”), is CTA’s own version of the kind of funky bar band rave-up of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Dance To The Music” or Archie Bell and the Drells’ “Tighten Up.” Midsong, one moves from the bar to the lounge for some lovely horn playing, and moments later one is in a concert hall listening to a screaming rock guitar solo by Kath.

And so it goes, “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” starts with an acoustic piano that is equal parts Erik Satie and Art Tatum, while the song itself is a bright, pop melody contrasted with a typically anti-establishment lyric. “Questions 67 And 68” combines a stately horn chart with some hot guitar and a musical cadence reminiscent of pop songs such as Jimmy Webb’s “MacArthur Park.” All through, there are the inventive horn charts, the sophisticated rhythm changes and startling musical juxtapositions, the alternating smooth (Lamm), soaring (Cetera), and soulful (Kath) singing that would become hallmarks of the classic Chicago sound.

Released in April 1969, Chicago Transit Authority was played by the newly powerful FM album rock stations, especially college radio. “AM radio wouldn’t touch us because we were unpackageable,” says Pankow. “They weren’t able to pigeonhole our music. It was too different, and the cuts on the albums were so long that they really weren’t tailored for radio play unless they were edited, and we didn’t know anything about editing. Actually, we released three singles off the first album. We edited three songs and released them, but AM radio was nowhere near ready for this kind of music, The album was an underground hit, FM radio was embraced by the college audiences in the late ’60’s. All of a sudden, the college campuses around the country discovered Chicago, and it was over. That was the beginning of the snowball. If you didn’t listen to Chicago, you weren’t hip. It was the college kids and word of mouth that made that album such an incredible, enormous mainstay on the pop charts.”

The album broke into Billboard magazine’s Top LP’s chart for the week ending May 17, 1969, and eventually peaked at Number 17. By the end of 1972, it had amassed 148 weeks on the chart (and that wasn’t the end of its total run), making it the longest running album by a rock group up to that time.

Chapter VI – Revolution

By December 1969, Chicago Transit Authority, still without benefit of a hit single, was a gold-selling album, and Chicago was a famous band. It changed their lives. “Your life dream is to have a hit record,” says Parazaider. “It was amazing because we were close friends, we had gone through all of this upheaval of leaving Chicago, moving to L.A. at a young age, leaving our families, just rolling the dice. We stuck real close together, kept everybody’s ego in check. I think for some guys in the group it was harder to cope with the success than others. I don’t think there were any of us that sat down around my kitchen table that day in February of ’67 and said, “Hey, our goal is to be famous.” The one good thing that seemed to help us is, we were the faceless band behind that logo.”

Indeed, though critics would always misinterpret their intentions, Chicago’s logo and its facelessness were very much in keeping with the style of the late ’60’s that valued group effort over individual ego. (To the delight of the poor folks who have to put up the letters on theater marquees , the group shortened its name simply to Chicago during its first year as a national act.)

In early December, Chicago flew to London to begin a 14-date European tour. Robert Lamm remembers it as a tour during which the band played for audiences that understood them and took them seriously for the first time. “Even we were not aware of how edgy and different the first album was,” he says. “We were just doing what we were doing, and we were hoping that it was different enough for people to notice it was different. But when international audiences heard the album, it just really stopped them cold. We played in clubs all over Europe, and the audience took to it much more readily than we had experienced anywhere in the States. When we came back, the album had gone gold, and we began headlining a little bit, but still the feeling was that American audiences didn’t really get it. They got that the band was becoming popular, but we didn’t have the sense that they were hearing the music for what it was. So, I think playing in Europe and being treated to a certain musical and artistic respect was eye-opening and really encouraging to the band. It made us realize that what we were doing was substantial, was artistic, and was respectable rather than just this pop commodity that we always felt like in the States, because of the audience, the press, and the way the record company regarded us. That success in Europe and the feeling that we got from the regard we were given as artists really told us in a way that has lasted to this day that this is more than just kid stuff.”

In between tour dates in August 1969, Chicago had found the time to record its second album. One of the first songs Lamm brought in for the album was “25 Or 6 To 4,” a song with a lyric Chicago fans have pondered ever since. What does that title mean? “It’s just a reference to the time of day,” says Lamm. As for the lyric: “The song is about writing a song. It’s not mystical.”

Perhaps the album’s most ambitious piece was Pankow’s “Ballet For A Girl In Buchannon,” which affected the tone of the whole LP. “The second record had more of a classical approach to it,” says Parazaider, “whereas the first one was really a raw thing. The second one seemed a little more polished.”

“I had been inspired by classics,” says Pankow of the Ballet. I had bought the Brandenburg concertos, and I was listening to them one night, thinking, man, how cool! Bach 200 years ago, wrote this stuff, and it cooks. If we put a rock ‘n’ roll rhythm section to something like this, that could be really cool. I was also a big Stravinsky fan. His stuff is classical, yet it’s got a great passion to it. We were on the road, and I had a Fender Rhodes piano between Holiday Inn beds. I found myself going back to some arpeggios, a la Bach, and along came “Colour My World.” It’s just a simple 12-bar pattern, but it just flowed. Then I called Walt into the room, and I said, “Hey, Walt, you got your flute? Why don’t you try a few lines?,” and one thing led to another. These things were disjointed, but yet I liked it all, and ultimately it was a matter of just sewing these things together, creating segues and interludes.”

The second album also saw the debut of a new songwriter in the band, although the circumstances under which he became a writer are unfortunate. During a break in the touring in the summer of 1969, Peter Cetera was set upon at a baseball game at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. “Four marines didn’t like a long-haired rock ‘n’ roller in a baseball park,” Cetera recounts, “and of course I was a Cub fan, and I was in Dodger Stadium, and that didn’t do so well. I got in a fight and got a broken jaw in three places, and I was in intensive care for a couple of days.”

The incident had two separate effects on Cetera’s career. The first was an impact on his singing style. “The only funny thing I can think about the whole incident,” he says, “is that, with my jaw wired together, I actually went on the road, and I was actually singing through my clenched jaw, which, to this day, is still the way I sing.”

The second effect of the incident was Cetera’s first foray into compositions. With a broken jaw, the singer had some silent time on his hands. “I was lying in my bed convalescing when they landed on the moon, and I grabbed my bass guitar and started this little progression on the bass, and started writing “Where Do We Go From Here.” I think Walter Cronkite actually had said that, and I thought, “Wow, where do we go from here?” So, l wrote it about that and about myself and about the world and about everything in general, and that was my first writing credit.”

The second album also took a more direct look at the political situation. Chicago had included chants from the Yippie demonstrators outside the 1968 Democratic Convention on its first album. The second album’s liner notes (penned by Robert Lamm) dedicated the record, the band members, their futures, and their energies “to the people of the revolution and the revolution in all of its forms.”

The development of Lamm’s political consciousness dated back to the band’s last months in their hometown in the spring of 1968. “Chicago actually was rather like a pressure cooker,” Lamm recalls. “During the last couple of months that we were there, there was a lot of unrest and there were National Guard troops in the streets. Now, this is before the Democratic convention, and the city was gearing up and already had a built-in fear of, if not Yippies, at least hippies, and we actually experienced it because we were playing clubs. You know, in Chicago you played pretty late, and a couple of us had run into situations where, leaving the club and having to walk through especially the Rush Street area when the bar’s were emptying out, there was a lot of angst directed toward longhairs. That was the first inkling that I had that something as simple as growing your hair long could be construed as a political statement. l think I really started paying attention then to the anti-Vietnam War protests, a lot of the rhetoric that was flying back and forth between members of our government and people who were well-known in show business and the media, talking about whether they were against the war or for the war. There was a lot of that kind of thing every day.”

The development of Lamm’s political consciousness dated back to the band’s last months in their hometown in the spring of 1968. “Chicago actually was rather like a pressure cooker,” Lamm recalls. “During the last couple of months that we were there, there was a lot of unrest and there were National Guard troops in the streets. Now, this is before the Democratic convention, and the city was gearing up and already had a built-in fear of, if not Yippies, at least hippies, and we actually experienced it because we were playing clubs. You know, in Chicago you played pretty late, and a couple of us had run into situations where, leaving the club and having to walk through especially the Rush Street area when the bar’s were emptying out, there was a lot of angst directed toward longhairs. That was the first inkling that I had that something as simple as growing your hair long could be construed as a political statement. l think I really started paying attention then to the anti-Vietnam War protests, a lot of the rhetoric that was flying back and forth between members of our government and people who were well-known in show business and the media, talking about whether they were against the war or for the war. There was a lot of that kind of thing every day.”

When the band moved to California and continued working up original songs, Lamm’s awareness of the world around him affected his lyric writing. In songs like “It Better End Soon” and “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?”, he reflected on the kinds of questions: political, social, and philosophical that young people around the country were starting to ask. “I’m not sure exactly what led me to the realization that I could write about things other than romantic topics,” Lamm says, “but I think just being alive in those times and watching that conflict in Asia unfold on television daily because Lord knows we all sat around and watched a lot of television, then the culture shock of moving from Chicago to California. And then the alternative press, the L.A. Free Press, was very much into the hot topic of revolution. It seemed that the generation of which I was a member and the generation which was peopling the new bands had a connection, and so it seemed natural to give voice to some of the thinking. As pinheaded (he laughs) as some of my opinions and those of some of my contemporaries may have been at the time, it felt really real, and also it felt like it was right, it was right that a lot of bands at the time were giving voice to the idea of the average person having a certain amount of power, and power maybe enough to stand up to the policies of the government and protest the war.”

At the same time, a confluence of the music business and the political movements was occurring. “We had begun in 1969 to play universities and colleges, Lamm recalls, “and very often those concerts were used as a springboard for political gatherings”. In other words, everybody would show up at the show, and then they would go and talk about either the anti-war effort or the more abstract concept of actual revolution. Then we played the pop festivals, which were a melting pot of everything, everything from free love to drug use to information dissemination about the anti-war movement, political climate, and social issues. So, it was really heavy stuff for everybody because nobody knew what was going on, but we all had a sense that there was some power available, just by the sheer numbers of us.”

Looking back, Lamm says, “I think there has been a revolution. You may argue with the term ‘revolution,’ but I think for those of us in our late teens or early 20’s, that sure was a sexy word.” Of course, the political activists at the time sought an idealistic and disruptive revolution that would replace “the system.” Lamm feels the actual revolution was less concrete, but perhaps ultimately more persuasive.

“In my view, the promise of paradise and peace on earth, that was something we all fervently believed was possible,” he says, “and what occurred was something more subtle. I believe that there was a revolution, and I believe that it happened so gradually that we didn’t realize what was going on. Even if you take something as mundane as music (he laughs), there’s a whole young generation of rap artists who are saying everything they want and actually expressing themselves politically and socially, and people of all cultures are hearing it, and that form of protest has flourished within the system, and it’s accepted, and for the most part it’s okay, except to extreme right wingers.”

The most obvious example of the social/philosophical revolution Lamm perceives are the changes brought about by the civil rights and anti-war movements so prevalent at the time. “I hate to harp on the whole racial thing, but I think that’s probably the easiest way to spot that things have changed immensely since the ’60’s,” he says. “Obviously, they’re not perfect for people of color in this country, but they are a lot different. We don’t think of black men the same way that we did in 1969. We just don’t. The stereotype has changed 180 degrees. Then, certainly a lot of the people who were on the front lines, whether civil rights movement, student revolt, or the anti-war movement, now are in the government. You could say they were absorbed by the system, but I think that looking back now, it was fantasy to think that you could replace the system. You couldn’t replace the system, but you could change the system.” So, perhaps the revolution, in at least some of its forms, has come to pass.

Chapter VII – Success

When it was released in January 1970, the second album, instead of featuring a picture of the band on the cover and a title drawn from one of the songs, had the band’s distinctive logo on the cover and was called Chicago II. From the start, Chicago took a conceptual approach to the way it was presented to the public. The album covers were overseen by John Berg, the head of the art department at Columbia Records, and Nick Fasciano designed the logo, which has adorned every album cover in the group catalog. “Guercio was insistent upon the logo being the dominant factor in the artwork,” says Pankow, even though the artwork varied greatly from cover to cover. Thus, the logo might appear carved into a rough wooden panel, as on Chicago V, or tooled into an elaborate leatherwork design, like Chicago VII, or become a mouth-watering chocolate bar, for the Chicago X cover, which was a Grammy Award winner.

And then there were those sequential album titles. “People always asked why we were numbering our albums,” jokes Cetera, “and the reason is, because we always argued about what to call it. ‘All right, III, all right, IV!”, Actually, the band never attempted to title the albums, feeling that the music spoke for itself.

In commercial terms, the major change that came with Chicago II was that it opened the floodgates on Chicago as a singles band. In October 1969, Columbia had re-tested the waters by releasing “Beginnings” as a single, but AM radio still wasn’t interested, and the record failed to chart. All of this changed, however, when the label excerpted two songs, “Make Me Smile” and “Colour My World,” from Pankow’s ballet and released them as the two sides of a single in March 1970.

“I was driving in my car down Santa Monica Boulevard in L.A.,” Pankow remembers, “and I turned the radio on KHJ and ‘Make Me Smile’ came on. I almost hit the car in front of me, ’cause it’s my song, and I’m hearing it on the biggest station in L.A. At that point, I realized, hey, we have a hit single. They don’t play you in L.A. unless you’re hit-bound. So, that was one of the more exciting moments in my early career.”

The single reached the Top 10, while Chicago II immediately went gold and got to Number 4 on the LP’s chart, joining the first album, which was still selling well. A second single, Lamm’s “25 Or 6 To 4,” was an even bigger hit in the summer of ’70, peaking at Number 4.

But instead of reaching into the second album for a third single, Columbia and Chicago decided to try to re-stimulate interest in the first album, and succeeded. The group’s next single was “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” which became their third Top 10 hit in a row by the start of 1971. “Up to that time, to be very honest, I don’t think people were really ready to hear horns the way we were using them,” says Parazaider. “But after we established something with horns ’25 Or 6 To 4,’ but actually ‘Make Me Smile,’ which was our first bona fide hit it seemed like it broke the ice and it became easier, and they accepted stuff that was recorded easily a year before.”

But instead of reaching into the second album for a third single, Columbia and Chicago decided to try to re-stimulate interest in the first album, and succeeded. The group’s next single was “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” which became their third Top 10 hit in a row by the start of 1971. “Up to that time, to be very honest, I don’t think people were really ready to hear horns the way we were using them,” says Parazaider. “But after we established something with horns ’25 Or 6 To 4,’ but actually ‘Make Me Smile,’ which was our first bona fide hit it seemed like it broke the ice and it became easier, and they accepted stuff that was recorded easily a year before.”

Ironically, Chicago’s belated singles success cost the group its “underground” imprimatur. “All of a sudden,” Loughnane recalls,” people started saying we sold out. The same music! Exactly the same songs!”

As January 1971 rolled around, once again Chicago had found time to record a new double album. “That third album scared us,” says Parazaider, “because we basically had run out of the surplus of material that we had, and we were still working a lot on the road. We were afraid that we were getting ready to record a little under the gun. But I don’t think it shows.” “That whole album was more adventurous in terms of instrumental exploration than the first two albums,” says Pankow. “Robert wrote a lot of in-depth stuff.”

Cetera also was flexing his muscles as a writer again. “Danny and I had got together one night, and I said, ‘I got this little thing that I’ve been working on,'” he recalls. The result was “Lowdown,” which became the second single from Chicago III. (The first was Lamm’s “Free.”) “I’m still proud of it,” Cetera says.

After the singles from Chicago III had run their course, helping the album to its chart peak at Number 2 and its gold record award, Columbia turned back to the first and second albums which were still in the charts, re-releasing as a single “Beginnings” backed by “Colour My World,” and then “Questions 67 and 68.” “They all become hits,” notes Loughnane, “to the point where radio said, ‘If you release something off that first album again, we’ll never play another one of your records.'”

All of this meant that, with its first three albums, Chicago had reached astonishing popular success. All three double albums were still on the charts throughout 1971, and hits came from each one. But how to top that? In October, Columbia released a lavish four-record box set chronicling the group’s week-long stand at Carnegie Hall, the previous April 5-10.

Chicago At Carnegie Hall holds mixed memories for the band members. Cetera feels that all the extra sound equipment inhibited the band’s performance. “Within the first two or three songs of the opening night, I’m singing and playing, and all of a sudden the level on my bass drops considerably,” Cetera remembers. “I turn around, and there’s a roadie out there messing with my knobs. I’m wondering, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ He goes, ‘Well, the sound truck told me to tell you to turn down, and since I couldn’t tell you, they told me to go out here and turn you down.’ That’s kind of what happened all the way along with everybody.”

“I hate it,” Pankow says. “The acoustics of Carnegie Hall were never meant for amplified music, and the sound of the brass after being miked came out sounding like kazoos.” Parazaider, however, notes with pride that the album marks a milestone for the group, that they were the first rock group to sell out Carnegie Hall for a week. “That was an exciting week,” adds Lamm, “to actually play in Carnegie Hall.”

Lamm got the chance to premiere “A Song For Richard And His Friends,” which was to have appeared on Chicago V. April 1971 was a long time before Watergate, and the resignation of a U.S. president was inconceivable, but that didn’t stop Lamm from offering a helpful suggestion to Richard M. Nixon. “I love that song,” Lamm says, “and later on I did a version of it for my first solo album, Skinny Boy though I didn’t end up including it where, in the tag chorus I add the line, ‘Thank you, John Dean.’ (Dean was the presidential assistant who blew the whistle on Nixon.) I’ve been told by one of the foremost psychics in Los Angeles that I’m psychic, I just don’t know it.”

Manager/producer Guercio had to fight Columbia to get the label to release the album, due to its manufacturing cost. He agreed to assume the extra expense if the album didn’t sell a million units. The bill never arrived. Chicago At Carnegie Hall went gold out of the box and has since been certified for sales of two million copies. (In fact, according to the current policy of the Record Industry Association of America, that each in a multi-disk set is counted individually, the three-CD album ought to be certified at six million copies.)

“When I listen to some of the Carnegie Hall album, it is really good,” says Loughnane. “There’s a lot of good material but there’s a lot of stuff that I was unhappy with and I didn’t think should be released, but that’s what it was. There was a history behind that record. The story, the marketing, all of that stuff went into it. The program, the pictures of the building, the diagrams, all of that was part of the charisma, and it worked. But I think we could do great live albums today. I would love to do that”

Though Chicago had made previous visits to Europe and the Far East, it embarked on its first full-scale world tour in February 1972. “We played 16 countries in 20 days,” recalls Walt Parazaider. “It’s that old movie: If it’s Tuesday, it’s Belgium. People said, “You went around the world, you played in all those countries.” I said, ‘Yeah, I remember some of the ceilings in some of the nicest hotels in Europe.” But we became an international success, and that was great, because people all over the world really enjoyed our music. And there’s nothing more flattering to people who create music than to have somebody singing your song when you’re in Germany or Australia or Japan. We marveled at it. We had to pinch ourselves that we were having all the success we were having.”

The high point of the tour was in Japan, where Chicago recorded another live album that was so superior to the Carnegie Hall album, there’s really no comparison. “The Japanese hooked up two eight-track machines together to make 16 tracks,” notes Parazaider. “The quality of the sound was excellent. “The LP was released only in Japan at the time, but it is now available soon on Chicago Records.”

Chapter VIII – Caribou Ranch

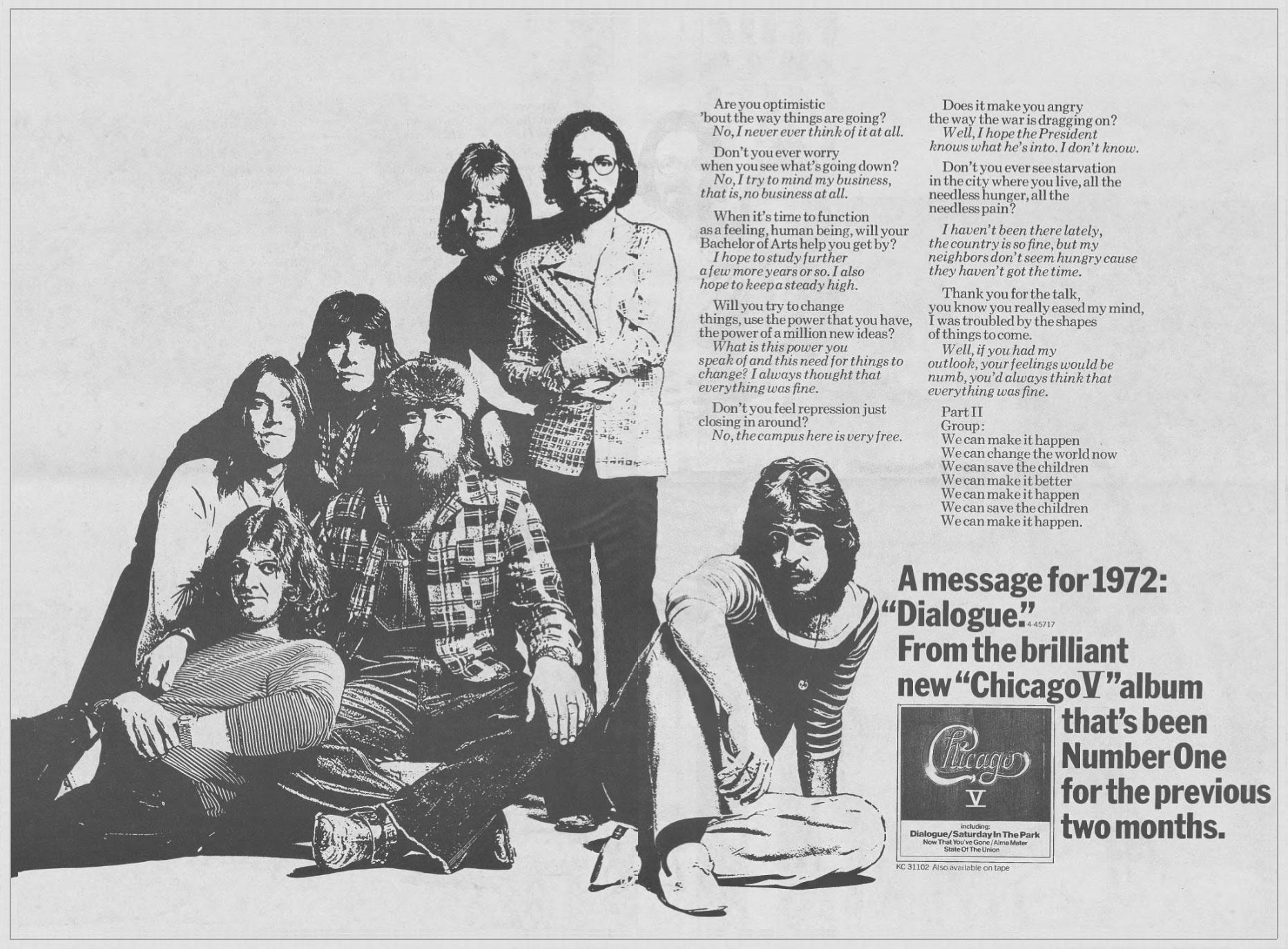

Chicago’s next studio album marked a change from its first three studio works in a number of respects. For one thing, Chicago V, released in July 1972, was only a single album. For another, the lengthy instrumental excursions of past records had been cut down, leaving nine relatively tightly arranged songs.

James Pankow offers an explanation for the change in the band’s approach. “About the time of that release, radio had started changing,” he notes. “FM radio became more commercial, and it started to deal with formats. This band has never said, ‘Let’s sit down and write an album of hit singles.’ That’s just not the way we do things.” But they knew things were changing.

Lee Loughnane suggests a little-known business reason why, with the exception of Chicago VII, the group stopped making double albums containing many compositions. “One thing that really changed music in a major way is the way that we were paid on song copyrights,” he says. “When we released all those double records, there wasn’t a limit on how many songs you could have on a record and how many copyrights you could get off of that record. Then the companies decided that they were only going to pay on ten copyrights per record no matter how many songs there were.”

The new copyright rule benefited some recording artists at a time when performers were recording extended compositions, sometimes fitting only one per side of a record. But Chicago, which previously had given its fans extra value for their money on double-record sets, suffered. “We wanted to be able to write songs that stretched and said everything we wanted to say,” Loughnane notes. “VII was the last double record, I don’t think you ever saw another double record, from anybody, as a matter of fact, because there was no reason. Monetarily, everybody lost from that.”

Chicago V is perhaps best remembered for Lamm’s “Saturday In The Park.” “I was rooming with him, and we were in Manhattan on the Fourth of July,” recalls Parazaider. “Robert came back to the hotel from Central Park very excited after seeing the steel drum players, singers, dancers, and jugglers. I said, ‘Man, it’s time to put music to this!'” Lamm had films of his adventures in the park and later edited the film and wrote “Saturday In The Park” as a kind of score. The album sold very well, topping the charts for nine weeks, the first of five straight Chicago Albums to reach Number 1. “Saturday In The Park” became the group’s first gold single, hitting Number 3.

As Chicago V was streaking up the charts, the band and its producer were taking a break from touring and recording by working on the film Elector Glide in Blue which was produced and directed by Guercio. The film was shot in Arizona and starred Robert Blake as well as Chicago members Terry Kath, Lee Loughnane, Walt Parazaider, and Peter Cetera. Guercio also wrote most of the music on the soundtrack, which was played by Kath, Parazaider, Loughnane, Pankow, and some of L.A.’s top studio musicians.

In October 1972, a second single from Chicago V, Lamm’s “Dialogue (Part I & II)” with vocals by Kath and Cetera, was released. “Dialogue” became an instant favorite with fans. Guercio, meanwhile, bought a ranch in Colorado and built a recording studio there that he dubbed “Caribou.” He was seeking to avoid the expense and restrictions of the New York studios and what he considered their outdated equipment. “We got a little tired of recording in New York, with maids beating on hotel room doors,” says Parazaider. “The sixth, seventh, eighth, tenth and eleventh albums were done up at Caribou Ranch, 8,500 feet up in the Rockies, about an hour’s drive outside of Boulder.”

The ranch was intended to facilitate uninterrupted work, but after two or three weeks holed up there, the city-bred guys would start to go stir-crazy. They couldn’t take all the nature and quiet. But the ranch did help focus the group, and the sound and the overall quality of the work improved. The first fruits of the new studio were released in June 1973, in the form of the single “Feelin’ Stronger Every Day” and the album Chicago VI. “Feeling Stronger Every Day” was about a relationship, Pankow says, but “underlying that relationship it’s almost like the band is feeling stronger than ever.”

Pankow’s “Just You ‘N’ Me,” which would be released as the album’s second single, and which would go gold and hit Number 1 in the Cash Box chart (Number 4 in Billboard), was one of Chicago’s most memorable ballads and very much a harbinger of the future. “‘Just You ‘N’ Me’ was the result of a lovers’ quarrel,” Pankow recalls. “I was in the process of becoming engaged to a woman who became my wife for over 20 years. We had a disagreement, and rather than put my fist through the wall or get crazy or get nuclear, I went out to the piano, and this song just kind of poured out. We wound up getting married shortly thereafter, and the lead sheet of that song was the announcement for the wedding, with our picture embossed on it.”

When Chicago gathered at the Caribou Ranch to record its seventh album in the fall of 1973, the initial intention was to do a jazz album, with the resulting “Italian From New York,” “Aire,” and “Devil’s Sweet” contributed by Lamm, Seraphine, Parazaider, and Pankow. On his own, Pankow brought in another gorgeous ballad, though this time his subject matter went beyond romance. ” “‘(I’ve Been) Searchin’ So Long’ was a song about finding myself,” he says. “I just had to talk about who I was and what I was feeling at the time. The ’70’s was a time for soul-searching.”

Cetera, who never claimed to be a Jazz musician, was discouraged about the original concept of the album, and also at his lack of participation as songwriter. He showed Guercio the lilting, Latin-tinged ballad “Happy Man.” “You know when people talk about these flashes of something coming?” Cetera asks. “They do, in fact. Every once in a while, a song will just come out of your mouth, the words and everything. It’s remembering it or having a tape player around when that happens that’s the important part. I wrote “Happy Man” about midnight driving down the San Diego Freeway on my motorcycle. It was the one and only song that I ever remembered, words and music, and I went home and sang it into a tape a day later.”

Cetera’s second last-minute contribution to Chicago VII is one of the Album’s best-remembered songs, “Wishing You Were Here.” “There’s two people that I always wanted to be,” Cetera confesses, “and that was a Beatle or a Beach Boy. I got to meet the Beach Boys at various times and got to be good friends with Carl Wilson.”

Cetera wrote the song in the style of the Beach Boys, who were at Caribou when it was to be recorded. Guercio, who had known the group since his backup days in the mid ’60’s, had recently taken over their management. Cetera asked the Beach Boys to sing on the bridge and chorus of “Wishing You Were Here.” “They said, ‘Yeah, we’d love to,'” he recalls. “So, I got to do the background harmonies with Carl and Dennis (Wilson) and Alan Jardine. For a night, I was a Beach Boy.”

As a result of the good vibrations between the members of both bands, it was agreed that a national tour would be fun and exciting for the bands and the audiences. The following summer, the Chicago-Beach Boys tour filled stadiums from coast to coast, nearly eclipsing the Rolling Stones, who were touring simultaneously.

Trumpeter Lee Loughnane was the next band member to write for the group. “Terry, Jimmy and Robert were the writers in the beginning, and then Peter and Danny started breaking into it,” he notes, “and then, by the seventh album, I started coming into it. I had just divorced and decided to write a song, and I presented ‘Call On Me.'” It was, he recalls, daunting company to try to break into: “These guys were very good at what they did, and I didn’t think they were going to like it.” Understandably, his band mates, also had been writing hit singles for five years, were more concerned with their own efforts. “Everyone went, ‘Yeah, that’s a good song, but listen to this,’ and listen to this,’ and ‘Yeah, check this out.” But Peter Cetera, who had had his own trouble breaking into the group’s songwriting fraternity, worked with Loughnane on “Call On Me,” which he ended up singing on the record. “He changed a couple of the words and the way he sang the melody in order for him to be able to play the bass and sing the melody at the same time because that’s the way he felt it,” Loughnane notes. “I appreciate his efforts, and we did make the song a hit.”

Chicago VII was preceded by the February 1974 single release of “(I’ve Been) Searchin’ So Long,” which become the band’s eighth Top 10 hit. “Call On Me” became their ninth, and “Wishing You Were Here” became their tenth, peaking at Number 9 in Cash Box, Number 11 in Billboard. The album was another chart topper. The year 1974 also marked the addition of an eighth member of Chicago, Brazilian percussionist Laudir De Oliveira, a former member of Sergio Mendez’s Brazil ’66. De Oliveira had first appeared on Chicago VI as a sideman. And in 1974, Robert Lamm released a solo album, Skinny Boy. Lamm wrote all the songs except “Temporary Jones,” which he co-wrote with Bob Russell, a celebrated lyricist who had worked with Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. Terry Kath played bass on the album, also contributing acoustic guitar on two songs. The Pointer Sisters sang on the title track, which also appeared on Chicago VII with horns added.

Chapter IX – Tragedy

Chicago began work on its next album August 1, 1974, at Caribou Ranch, and the results started to emerge in February 1975, with the release of the single “Harry Truman,” Lamm’s tribute to a president America could trust and a reference to the recently concluded Watergate scandal. Pankow wrote the sentimental “Old Days.” “It’s a memorabilia song, it’s about my childhood,” he says. “It touches on key phrases that, although they date me, are pretty right-on in terms of images of my childhood. ‘The Howdy Doody Show’ on television and collecting baseball cards and comic books.” “Old Days” was a Top 5 hit when it was released as the second single from Chicago VIII, which appeared in March 1975.

The year 1975 marked an early commercial peak in Chicago’s career, a year during which the band scored its fourth straight Number 1 album, a year when all its previous albums were back in the charts. Chicago’s worldwide record sales for this single year were a staggering 20 million copies. The group returned with an all-new album in June 1976, when it released Chicago X. (Chicago IX had been a greatest hits collection.) The big hit from the album was a song that just barely made the final cut, Peter Cetera’s “If You Leave Me Now.” “That was one of those magical ‘We need one more song (situations),'” Cetera recalls.

Three months later, Parazaider remembers, “I’m sitting around a pool, and a song comes on, I’m going, ‘That’s a catchy tune. Where have I heard this before?’ The next thing, they go, ‘That’s Chicago’s latest release, “If You Leave Me Now.” The main point of the story, outside of me being a dummy, is that often songs that just made the album end up being some of the biggest hits.”

“If You Leave Me Now” streaked to Number 1, Chicago’s first Billboard singles chart topper. It also topped charts around the world. Chicago X won the band its first platinum record (the awards had only just been inaugurated that year), selling a million copies in three months. Afterward, the ballad style of “If You Leave Me Now” increasingly seemed to become the preferred style of Chicago’s audience and radio listeners. “That drove me crazy,” says Lamm. “I know it drove Terry crazy, because that isn’t what we set out to be and it isn’t how we heard ourselves.”

By 1977, after eight relentless years of touring and recording, strain was beginning to show. “We’d cut down the touring from 300 dates to 250, down to 200, which is still a lot of days on the road,” says Parazaider. “But let’s face it, we were booming.” In January, Chicago undertook another world tour, and the band was in Europe when they won a Grammy for Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Duo, Group or Chorus for “If You Leave Me Now.” They also took Grammys for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocals and Best Album Cover.

By 1977, after eight relentless years of touring and recording, strain was beginning to show. “We’d cut down the touring from 300 dates to 250, down to 200, which is still a lot of days on the road,” says Parazaider. “But let’s face it, we were booming.” In January, Chicago undertook another world tour, and the band was in Europe when they won a Grammy for Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Duo, Group or Chorus for “If You Leave Me Now.” They also took Grammys for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocals and Best Album Cover.

In September, Chicago XI was released, its most notable song being “Take Me Back To Chicago,” written by drummer Danny Seraphine and David “Hawk” Wolinski. It has a darker theme than may be immediately apparent. “‘Take Me Back To Chicago’ is about Freddy Page, the drummer in the Illinois Speed Press who died tragically,” says Guercio. Like Chicago, the Speed Press had been brought to L.A. from the Midwest by Guercio in 1968. “Illinois Speed Press had the best shot, had the biggest budget, had the first record, and totally could not get along,” he recalls.

The mounting tensions between Chicago and Guercio finally erupted. The split between group and manager had been a long time coming. Guercio had exerted a powerful control over the members of Chicago, especially in the early days, and as they became stars, it probably was inevitable that they would begin to chafe under his harsh leadership. “It started happening with the tenth record,” says Parazaider. “He didn’t want us to learn any of the production techniques. He’d go to sleep at nine o’clock, and we’d start producing the records ourselves. Or trying to. I think if you’re the producer of your album, you have a fool for a client. You can’t be that objective about what you’re doing on both sides of the glass.”

“As I look back, I was much too hard on these guys,” Guercio admits. “I felt a thoroughbred by committee is a goddamn mule. I totally manipulated them for my own ends as well as theirs, whether they understood them or not.”

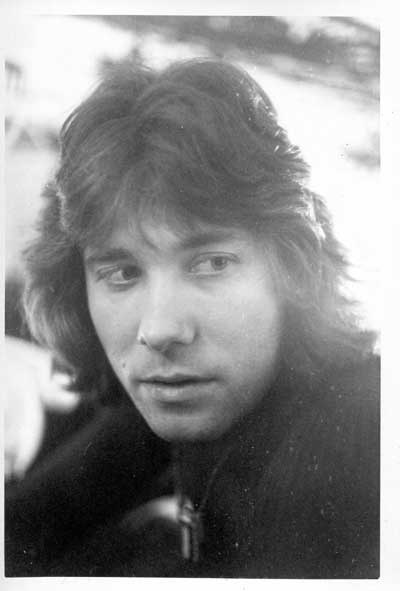

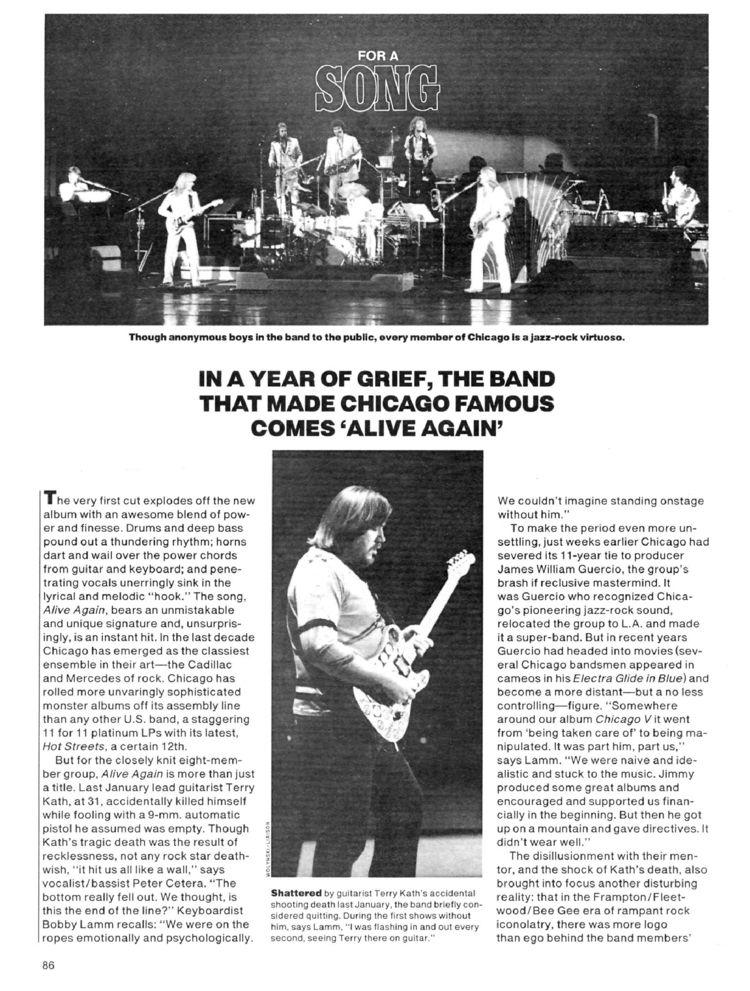

In the short term, little seemed changed. “Baby, What A Big Surprise” sailed into the Top 5, and Chicago XI was certified platinum the month after its release. But only a few months later, the band would be devastated by a terrible loss. On January 23, l978, Chicago guitarist and singer Terry Kath died from an accidental gunshot wound. “Terry Kath was a great talent” says Jim Guercio, who worked with him on a solo album that was never completed. “Hendrix idolized him. He was just totally committed to this band, and he could have been a monster (as a solo artist).”

Kath’s death devastated Chicago, and the band considered breaking up. “Right about there was probably what I felt was the end of the group,” says Peter Cetera. “I think we were a bit scared about going our separate ways, and we decided to give it a go again.” A short time after Kath’s death, “Take Me Back To Chicago,” which by now seemed as much about Kath as about Freddy Page, was released as a single.

If the band was going to continue, it would need a new guitarist, and auditions began in earnest in the spring of 1978. “We felt that we were being left behind by the new music,” says Cetera, “and we thought we needed a young guitar player with long hair. We sat through I don’t know how many guitar players, but I’m sure it was 30, 40, or 50 guitar players. Toward the end, Donnie Dacus showed up. He played a couple of songs right and with fire, and that’s how he was in the group.”

Chapter X – New Era

The band went to Miami’s Criteria Studios with producer Phil Ramone, who had mixed many of their singles and television specials. “Hot Streets was a scary experience,” says Pankow of the album even band members occasionally slip and called Chicago XII. “Guercio was no longer in the picture, and neither was Terry. But Phil Ramone believed in the band from the beginning. After recovering from the enormous tragedy of losing Terry, I think we did a damn good job.”

Perhaps the album’s most notable song is the up tempo “Alive Again,” which was also the first single. “If you read between the lines, it’s a tribute to Terry Kath’s passing,” says Pankow. “That’s the first song we recorded subsequent to Terry’s death. It’s the band saying we’re alive again, and Terry’s looking down on us with a big smile.”

To mark the new era, Chicago changed their album design. Hot Streets, released in September 1978, was the first Chicago album on which a picture of the group was the dominant feature of the cover. “After the album came out, the record company did a survey,” says Pankow, “and 90 percent of the people surveyed didn’t give a shit about what we looked like, much to our chagrin. They wanted to see the logo. The music has always spoken for itself, and the logo has as well. It’s like Coca-Cola: When you see it, you know what it is,” Hot Streets was certified platinum before the end of October, and produced two top 20 Singles in “Alive Again” and “No Tell Lover.” “It got us over the letup,” Parazaider says, “and we proved to ourselves we could go on and sell records.”

To mark the new era, Chicago changed their album design. Hot Streets, released in September 1978, was the first Chicago album on which a picture of the group was the dominant feature of the cover. “After the album came out, the record company did a survey,” says Pankow, “and 90 percent of the people surveyed didn’t give a shit about what we looked like, much to our chagrin. They wanted to see the logo. The music has always spoken for itself, and the logo has as well. It’s like Coca-Cola: When you see it, you know what it is,” Hot Streets was certified platinum before the end of October, and produced two top 20 Singles in “Alive Again” and “No Tell Lover.” “It got us over the letup,” Parazaider says, “and we proved to ourselves we could go on and sell records.”

The band went on the road to support the album and did a concert tour with a small orchestra conducted by Bill Conti, who had risen to fame as the Oscar-winning composer of the soundtrack to Sly Stallone’s Rocky. Ultimately, Donnie Dacus didn’t work out and left the band, though he remained through the 13th album. The personnel problem was compounded by a musical one: As the late ’70s wore on, the sophisticated, jazz-rock, pop-oriented style of Chicago was being squeezed by disco on one side and punk/new wave on the other, each of them making the band seem unfashionable.

Responding to pressure to change the sound, Chicago 13 , which was released in August 1979, contained the song “Street Player,” which has a disco flavor. According to Parazaider, the album “hit the wall at 700,000 copies, a good sale for some, but very disappointing by Chicago’s standards.

At this time, Chicago signed a new, multi-million dollar record contract with Columbia. “There was no way either party should have made that deal,” says Lamm. “It created a lot of animosity at the company.” After Chicago XIV suffered disappointing sales, Columbia bought the group out of the remainder of the contract and released Greatest Hits, Volume II, counted as the 15th album.

To replace Donnie Dacus, Chicago had hired guitarist Chris Pinnick as a sideman. “Chris came closest to Terry’s rhythmic approach,” says Lamm. Laudir De Oliveira also departed the group at this point.

Chapter XI – The Next Hurdle

In the fall of 1981, Chicago asked Bill Champlin, a noted Los Angeles session singer and musician, to join them. “They needed a little bit of guitar work,” says Champlin, “and they needed somebody to sing Terry’s stuff.” “Bill might come the closest to Terry’s gutsy lead vocals,” says Parazaider.

Champlin had had a long career already. Born on May 21, 1947, in Oakland, he grew up in various California cities, settling in Marin County north of San Francisco when he was l2. Champlin’s mother played the piano and wrote songs, and he took piano lessons between the ages of three and five. “I was reading music before I was reading English,” he recalls. But it wasn’t until the advent of Elvis Presley and early rock ‘n’ roll that he took up the guitar and began to think of music as a future profession. “I’d had enough early training with piano that it wasn’t really hard for me to get back into it,” he notes, “and then I took a million music classes in high school. I was trying to learn as many instruments as I could because I wanted to get a masters in music.”

While in high school, Champlin was part of the Opposite Six, a band with two horns that played James Brown-style R&B. “We were the house band at this one community center,” be says, “so we backed up a lot of the acts that they brought in, like Jan and Dean and the Righteous Brothers.”

The Opposite Six evolved into the Sons of Champlin, which released a single on Verve in 1965. Champlin was attending the College of Marin in pursuit of a music degree at the same time, when he got some good advice. “My theory teacher, Larry Snyder, suggested that I drop out because he said I was doing better music with my band than I was ever going to do in school,” Champlin recalls.

The Sons of Champlin became one of the original San Francisco rock groups of the 1960’s, releasing seven albums, though they never became a major commercial success. Champlin quit the band and moved to Los Angeles in 1977, where he began doing session work. Also a songwriter, he co-wrote “After The Love Has Gone,” which was a hit for Earth, Wind & Fire and a Grammy R&B Song of the Year. He would win a second R&B Song of the Year Grammy for co-writing “Turn Your Love Around,” which became a hit for George Benson just after be joined Chicago.

Champlin had worked closely with Canadian producer and songwriter David Foster, whose other clients had included Hall and Oates and the Average White Band. “A lot of people think Foster brought me into Chicago,” Champlin notes, “and it’s the other way around, I actually brought Foster into Chicago.” Champlin knew Danny Seraphine, and Seraphine went to him for advice about Foster, who had been considered as a possible producer for the 14th album before the job went to Tom Dowd and was now being considered for the 16th album. “Danny called me and said, ‘What do you think of David Foster as a producer?’,” Champlin recalls. “I said, ‘You’ll probably end up rewriting a lot, but I think Foster would be great for you guys.”

As Champlin had predicted, David Foster took a strong hand in the making of Chicago l6, co-writing eight of the album’s ten songs, including “Hard To Say I’m Sorry,” which became a worldwide Number 1 single when the album was released by Full Moon/Warner Bros. Records in June 1982. The album went into the Top Ten and sold a million copies.

“We had a resurgence then,” remembers Parazaider. “I had a kid come up to me and say, ‘I have your first record, would you mind signing it?’ This was somewhere in North Carolina. We were going on-stage, and I told her I would sign it after the show. And what she had was the Chicago l6 album. She had no idea about the others that came before it. The reality hit, we had gained another generation.”

“We had a resurgence then,” remembers Parazaider. “I had a kid come up to me and say, ‘I have your first record, would you mind signing it?’ This was somewhere in North Carolina. We were going on-stage, and I told her I would sign it after the show. And what she had was the Chicago l6 album. She had no idea about the others that came before it. The reality hit, we had gained another generation.”