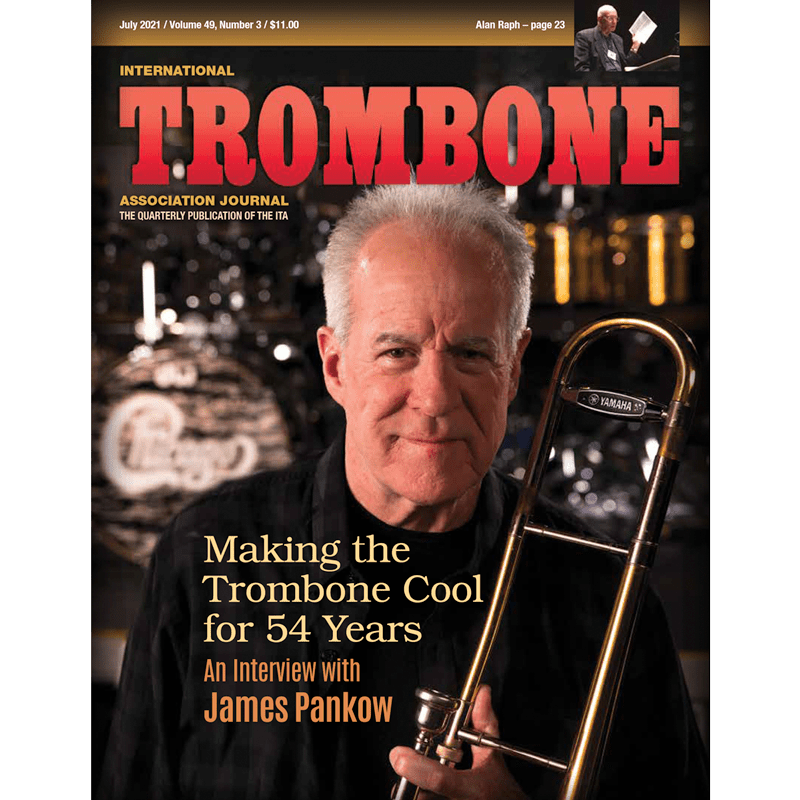

Making the Trombone Cool for 54 Years

An Interview with James Pankow by Kevin M. McManus

James Pankow is among the most influential and multitalented musicians of all time. A founding member of the rock band Chicago, Jim has written and arranged songs that have become the soundtrack of our lives. Chicago has recorded more than thirty-seven albums, sold over 100 million units worldwide, with twenty-three gold, ten platinum, and eight multi-platinum albums. Chicago was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2014 and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2016. Jimmy Pankow is the recipient of the International Trombone Association’s 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award.

Kevin: How did you become a trombonist?

Jimmy: I’ll be honest with you; I was not focused on becoming a trombonist. I wanted to play the drums, guitar, or saxophone. I wanted to be cool with my peers! My parents took me to the tryouts in the church basement and they had all the instruments laid out on tables. I was standing in line to try the drum kit with about fifty other kids. My parents didn’t have all day, so with the help of the band director, they approached me with the suggestion of trying out a less popular instrument. There was nobody, I repeat, there was nobody standing at the table with the trombone! And they said, “What about that instrument over there?” And I said, “That thing? I’m not playing that sewer pipe—that ain’t cool!” But might makes right, and the three of them persuaded me to try it out and take it home.

Kevin: So when did you develop your connection with the trombone?

Jimmy: I didn’t really start bonding with the trombone until I got to the point where the slide and slide technique became interesting. I started realizing that I could play the same notes in different positions and that my arm didn’t have to be so busy. I got to the critical point where I would hear something in my head and I’d be able to reproduce it on the horn. I realize that I had a gift called “an ear”—which became very important, if not critical, in my musical growth. I didn’t need notes on paper, I could simply hear something and reproduce it on the horn. When I could play along with records is when it started getting fun.

Kevin: Which records did you play along with?

Jimmy: My father brought home a J.J. Johnson record that blew me away! It was the first time I heard a trombone player that was modern and cool. He had great legato, tonguing, and a mellow sound. I’m going, “This guy is hip!” I took that record to the basement and shedded to it. One day, I nailed it to the point where I could play along with J.J. Certainly not as amazing as J.J.’s technique, but I could pretty much copy him. When my father came home from work, I said, “Dad, I have a surprise for you.” I brought the J.J. Johnson album upstairs and my dad put in on the Victrola in the living room. I played along with J.J. note-for-note and my dad started welling up.

Kevin: Tell me about your dad.

Jimmy: My dad was my first true mentor. He had played piano for about twelve years. But he burnt out because his teacher was only interested in playing Beethoven, Mozart, or Bartok, perfectly. His teacher was too consumed in making himself and his students look good in recitals.

My father would get his hands slapped any time he tried to stretch out. It was discipline, discipline, discipline— no fun allowed! So my dad said, “This isn’t any fun, man! If I can’t have fun, I’m done.” So he moved away from it, tragically, because of his gift, his ears. His ears were huge! Huge! My dad could have been a giant in music but he was slapped down at every opportunity and it ruined him. But he figured if he couldn’t enjoy that journey then maybe he could celebrate mine. And it inspired me to take advantage of the opportunity that he never had a chance to enjoy.

So, back to the story. After dinner every night, he’d come home from work and the two of us would go into the living room and he’d play records for me. One night it would be Count Basie. Another night it would be Woody Herman. Yet another night it would be Stan Kenton. So we had a musicology session after dinner every night. And he’d ask me, “Do you hear this? Do you hear that? Do you hear what the trombones are doing? Do you hear how they’re playing with the saxes, underneath the trumpet melody? Do you hear how that synergy is working? Do you hear how they’re complimenting each other?” Through those listening sessions, he taught me many ways to hear music.

Kevin: Did your father get to hear you perform as a professional?

Jimmy: Yes! He enjoyed my success all the way into the highest points of my career. He got to see the Grammy awards and the Gold records. He was so proud of me when the band made it. I think he may have been more excited than I was. Before we recorded our first album, we were playing nightclubs in Chicago. My dad would come to the clubs before he went home from work, just to check us out. The guys in the band at first were asking, “Who is that guy? He’s mouthing every note we’re playing and he’s boogieing on the bar stool. I mean, the guy is going nuts. Who is that guy?” And I said, “That’s my dad.” And the guys said, “You’re shitting me. He is grooving! Your dad gets it.” And I said, “You’re Goddamn right he gets it! That’s where I got it. He hears it all.”

Kevin: Aside from your dad, who were your other teachers?

Jimmy: We lived on the north side of Chicago and were close to Notre Dame High School for Boys, which had a band director named Father George Wiskirchen. Father Wiskirchen was amazing! He wrote the book on high school jazz. His bands won the state jazz band competitions every year and were the yearly guests of honor at the Notre Dame University Collegiate Jazz Festival. Wiskirchen was instrumental in my education and taught me how to swing. He taught his bands how to groove and if anyone started playing squarely or didn’t swing, he’d say, “Hey! If you can’t swing, you’re out of here!” I mean, it was a four year program that most definitely planted the seeds and launched me into higher learning on the horn, music, and my career. I will always be grateful for Father Wiskirchen.

Kevin: Who were your trombone heroes?

Jimmy: There are a lot of players that have influenced me over the years. I love Carl Fontana; he’s amazing! Subconsciously, I’ve probably emulated his style even more than J.J.’s. I have a kinship technically with Fontana’s approach. Others were Frank Rosolino, Urbie Green, Kai Winding, Bill Watrous, Dick Nash, Slyde Hyde, Bob McChesney, and Steve Wiest.

Kevin: I’ve heard that Harold Betters was one of your influences. Is that true?

Jimmy: Yeah, Harold Betters! He’s from Pittsburgh. He was essentially a jazz trombonist who had a crossover hit with “Do Anything You Wanna.” In fact, when we were in Pittsburgh in the ’70s, Harold was showcasing across the river at City Center. We were playing at the Civic Arena and had a night off. So we jumped in a cab and went over to the club to hear him. He was a great entertainer and played his butt off! He was probably in his late thirties or early forties at that time. He was a bone player that had the vision to break away from traditional jazz and do his own thing—he stepped out. When you talk with him, please pass along my sentiments, and tell him that I was very aware of him and his courage to break the rules—to groove in the pop mainstream—and I personally thought it was hip.

Kevin: Tell me about your college career.

Jimmy: Father Wiskirchen encouraged me to audition at Quincy College, where I received a full tuition scholarship. I majored in music education at the behest of my parents. At various times, upperclassmen would say, “Jimmy, don’t teach, play! Take your horn out there and play for people.” So after one year at Quincy, I went back to Chicago and put together a small combo.

Kevin: What was the name of your combo?

Jimmy: The “Jivetet.” It was influenced by Cannonball Adderley and his Jive Samba. We did a lot of Cannonball, Crusaders, Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, and McCoy Tyner. We basically did covers of all of the small combos of the day.

Kevin: What was the instrumentation?

Jimmy: It was a tenor sax, trombone, and rhythm section. But on some gigs, we added a trumpet. Which may subconsciously be why I approached the Chicago horn section with that instrumentation. The Jivetet started gigging all over the city of Chicago and we were making some pretty good money. And then I started thinking, “Hey, this is pretty cool. I can make a living playing this horn.”

Kevin: Who was your trombone teacher at Quincy?

Kevin: Who was your trombone teacher at Quincy?

Jimmy: The Dean of the Quincy College Music School, Charlie Winking. He was a great teacher but was brutal! Did you ever hear of the Blazhevich Clef Studies, Kevin?

Kevin: Yes.

Jimmy: OK. He forced me to play through those studies and if I wasn’t spot on, he’d make me do it again. He’d put the metronome on and I had to play it at tempo. Alto clef going by, tenor clef going by, bass clef going by . . . “That wasn’t good enough; you’ll have to do it again.” I hated the guy! [Laughing!] Mr. Winking demanded perfection and I couldn’t cheat—I had to practice. He taught me discipline, which serves me—which serves all of us. He was a great teacher.

Kevin: How did you transition from Quincy College and Mr. Winking?

Jimmy: Well, I called Mr. Winking and said, “I’m not coming back for my sophomore year.” And he was crushed because, unbeknown to me, he had planned on moving me from bass trombone, which I played in the Quincy Orchestra, to first trombone. But I told him, “Mr. Winking, I’m working. I have steady gigs and I don’t want to give them up. I have an agent and am in the Union. It’s all happening.” Mr. Winking said, “I can’t argue with you, Jim. You’re a student in music school to ultimately make a living playing or participating in music at some level and you’re already doing that. You’re making a living and I couldn’t ask you to abandon that because it would not be reasonable. So all I can do is wish you luck and tell you that we are going to miss you. But I understand why you can’t come back now.”

Kevin: Sounds like he was a great man and had your best interests in mind.

Jimmy: You know, something else about Mr. Winking. After our first album came out, Mr. Winking told Father Wiskirchen, “Father George, Chicago’s music is pioneering stuff and I think Jimmy’s true gift is composing and arranging. I think his legacy will say that. I think his gift is more in creating music than performing it.” And you know, Kevin, I think he was right.

Kevin: Pertaining to your college career, what happened next?

Jimmy: As providence would have it, I enrolled at DePaul University for my sophomore year and that’s where I met Walt Parazaider [Chicago saxophonist] and Lee Loughnane [Chicago trumpeter]. I’d be in the practice room shedding and I’d see this face in the window all the time and I’d say, “Who is this guy? He keeps looking into my practice room window.” Finally, he knocked on the door and came in and said, “How ya doing, man? My name is Walt Parazaider and I really like your playing. I have a proposition for you.” I said, “Well, OK. What’s up?” And he said, “What do you think about the idea of putting a rock band together and being part of a horn section that was a main character in the band? Not just backup players, on a riser, but a horn section that is upfront, center, kicking ass, instrumental, but playing Rock and Roll.” I went, “What? That’s amazing! How do we do that?”

Kevin: Did you graduate from DePaul?

Jimmy: DePaul was a launching pad. Many students go to college and don’t earn a degree because opportunity knocks. So, no, I didn’t graduate from DePaul. Timing is everything and we, as a band, had to move to California where the music was happening. And the rest is history.

Kevin: Can you talk about how your approach to the trombone has affected your horn section writing?

Jimmy: I considered my real focus on the trombone not to be my technical prowess or the ability to play every note on the page, but a stylistic approach. This led to my horn section writing with a trombone lead. My style, which is evident when I solo, my glisses into notes, my attacks, my personalized approach, is making the notes sound like the vocalists. [Jimmy sings.] I put those inflections into the style to sound vocal. Which makes this mechanical instrument sound human—it gives the trombone a human quality. And that’s what goes into our approach as a horn section. I call it, “the grease.” We grease the notes to make them sound human. So when the vocal leaves off and the horns come in, it’s seamless. [Jimmy sings.] I’m putting that human aspect into the horn parts so it’s emotional.

Kevin: How did you become the horn arranger?

Jimmy: My approach to arranging was inherited. When we formed the band back in 1967, I was given the baton because of my background in jazz and my remedial arranging for the Jivetet. But my responsibility with Chicago really involved the question, “How do I take this approach to brass and make it unique? How do I create something different?” That was a question I had nothing else to baseball off of. Because this idea had never happened before—a Rock and Roll band with an indigious horn section.

When Chicago came about, R&B was essentially Top 40 and all the hits on the radio had horns in the background. But they were kicks and riffs that were frosting on the cake. What we did was incorporate this horn section into the music in a way that it was a main character, an integral part of the arrangement.

Kevin: With this new writing approach, when did Chicago find its unique voice?

Jimmy: In the course of our night club appearances, we began to discover our own voice. Original material started to emerge. And slowly but surely, we started including our own material in the sets. As we started doing that, we started getting fired from one place after another because club owners didn’t want to have anything to do with our songs—they wanted to hear Top 40. That all changed when a place opened on Rush Street in Chicago called Barnaby’s. That was the first club that I know of in the Midwest that actually encouraged alternative music. They wanted to hear new stuff; they wanted to hear the “next thing.” Barnaby’s embraced our music.

Kevin: What was the next step in the band’s development?

Kevin: What was the next step in the band’s development?

Jimmy: So, having been fired from basically every place in the city, we knew that we had to make a decision. Do we want to be the biggest Vegas show band in the Midwest, or do we want to take it to the next level and explore our own sound? If the latter, we couldn’t stay in the Midwest. We had to go to where the current music scene was happening—L.A.

At that point, we put everything in small trailers and drove across the country. We eventually became the house band at the Whiskey A Go Go on the Sunset Strip, which, by the way, is still there but now called The Whiskey. They became family and allowed us to rehearse and perform there whenever they didn’t have a national act booked. The record labels would come into the Whiskey to hear what new things were happening, and perhaps, sign a new artist.

At any rate, we were the opening act for Albert King, cousin of B. B. King. We were in the dressing room waiting to come back on for the next set. As we were about to leave the room, we saw a guy standing in the doorway and went, “Holy shit, that’s Jimi Hendrix!” Jimi had heard our last set and came upstairs to our dressing room and said, “You guys have a horn section that sounds like one set of lungs. And you’ve got a guitar player that’s better than me. Do you guys want to go on the road?” And we said, “With you? Yeah!!!” So we went on the road and became the opening act for the Jimi Hendrix Experience. That was our first national tour and the exposure was unbelievable. We’d come on as the opening act and the crowd would be chanting, “We want Jimi! We want Jimi!” And we said, “Shut the hell up and listen.” And they did.

But back to your original question, as soon as we made the move and started this new focus on original material the question was, “What do we do with the horns?” That was the new frontier.

Kevin: How did you go about that process?

Jimmy: As guys in the band started sketching out original ideas, I would get cassettes with rough tracks. I’d then grab my trombone and “doodle” melodic ideas around the lead voice that would complement and lead into the vocal and leave off where the vocal ended. Basically, I transcribed my trombone doodles and voiced them where appropriate. They acted as a bridge to where the lyric picked up again. So the horn section was used as a device to fill in holes melodically.

Whereas if you took the horn material out of the track, it would be full of holes; it would sound empty. The horns weren’t just “frosting on the cake” like horns were up to that point. The horns were a melodic statement and many of our parts are unison. It’s basically another lead vocal that continues the melody and theme of what the actual vocals are doing. So the vocals and brass are working in concert with one another. It’s all crafted to allow and identity the horns section as a main character in the story. So intrinsically, Chicago has also been and will continue to be a rock band with a lead voice in the horn section. And, of course, that evolved and keeps evolving.

Kevin: You not only have inspired many musicians but have created gigs for us through your writing. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Jimmy: That’s very kind of you to say that. You know, Chicago was a pioneer. By creating this pop approach, it created gigs for wind players to be able to play the music of their peers. To be able to play modern music, pop, fusion, rock-jazz, we opened up a genre for horns that never existed. Before us, you could play in an orchestra, concert band, marching band, jazz ensemble—a more “classically” approached ensemble. There wasn’t any room for trombone players to boogie—to get up there and be a Rock and Roll musician. It’s really gratifying, Kevin, to know that I was part of a movement, if you will, that created work for players, and I’ll never ever not be humbled when I hear it. The most incredible compliments, the most meaningful compliments are from peers, like yourself, and I am humbled beyond belief.

Kevin: You frequently write dense chords with a lot of chromatic alterations. How do you pare down five, and sometimes six, note chords for live performance with only three horns?

Jimmy: I have to economize and make the three notes that we are playing the most effective. I usually don’t voice the root or the fifth, but I do need to voice the seventh, raised ninth, flatted fifth, or sometimes the minor third. I use key notes and hope that the keyboard and guitar guys will fill in the blanks.

I always make sure the three horns make the chords sound full. And, if you noticed in much of it, if not most of it, the bone is upstairs. When I write an ensemble, it starts as a bone solo and then I voice it out. It’s a lead bone. And I voice the trumpet in the staff and the tenor above the staff, which puts the tenor and the trumpet in the same range. So that equals “tight” voicing because we’re all essentially in the same register. But then, when I want open voicing, I’ll keep the bone down and I’ll put the trumpet upstairs and the sax in the middle. For a lot of the stuff, the open voicing is critical because the notes of the chord are so dissonant, and the distance smooths out the rub. And that’s just a matter of doing it long enough and trusting yourself.

Kevin: Do you play differently in the studio versus live?

Jimmy: Good question. Yes. In the studio, we are a lot more technically focused. If you don’t phrase and focus on pitch and rhythm, you’re never going to be able to double or triple track. So when we are in the studio, we are much more focused on accuracy. If you have a fluff on stage, who cares—if it swings, it doesn’t matter. But in the studio, it does matter. Everybody has to phrase together or else you’ll never be able to double or triple it.

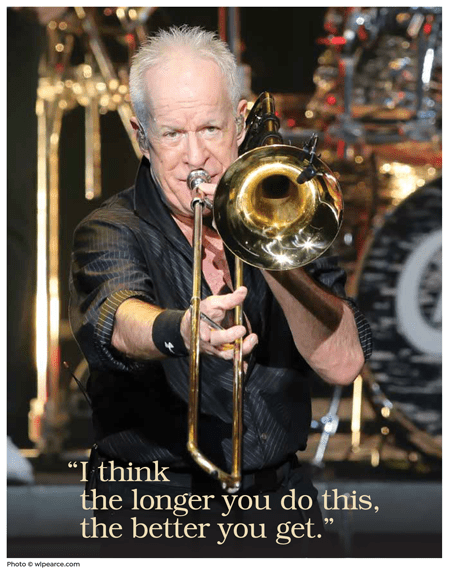

Kevin: How do you deal with the repetitiveness of live performances?

Jimmy: People often ask, “How can you play the same music every night and do it with enthusiasm?” It’s because every night we are trying to perform each note as exact and as perfectly as possible. We’re not up there doing a loose rendition— we’re doing the record! Our fans are hearing the songs they love, note-for-note, on a state-of-the-art sound system. It’s like being able to listen to a record on steroids, and they’re experiencing that record performed live! There’s no smoke and mirrors. There’s no lip-synching. These are veteran musicians performing this music before your very eyes. And we owe it to our fans to do an exact, faithfully executed, rendition of those songs that they’ve paid to hear.

Kevin: We’re all longing for the moment when we can share our gifts on the stage, again.

Jimmy: You know, Kevin . . . music and musicians have always been extremely valuable when tragedy strikes. After 9/11, those audiences couldn’t wait for the salve of music to soothe their hearts and souls. Music is food for the soul— it’s the language of the soul. It doesn’t matter what language you speak, how old you are, what race you are: music is the international food for our souls. It’s an incredible gift making a living in a profession that’s all about spreading the “feel good” vibe. To stay connected with our audience we’re releasing a DVD, which is a compilation of the best live performances. But nothing replaces the live concert performance. The hand-to-hand combat, I deeply miss it.

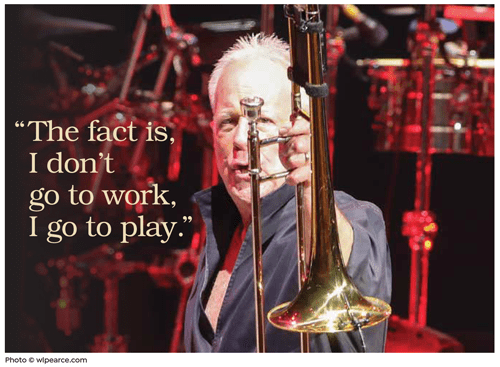

Kevin: I can tell that you love sharing music with your audiences.

Jimmy: I continue to be on the road eight months a year and people say, “Jim, I don’t know how you do it.” And I respond, “On the contrary, I don’t know how NOT to do it!” If I retire from performing, I would stop participating in my first love. Because having a career in music is a gift. The fact is, I don’t go to work, I go to play. I can’t wait to go and perform for people—to get onto that stage and hear that roar of approval. I mean, to make a living putting smiles on peoples’ faces is really a lucky break. The fact that we’ve been able to do it for over half of a century, is, in itself, amazing. And it’s more exciting now than it ever was. Because, as you get older, all the pop-star stuff fades away because it’s not meaningful. But what remains is the joy of the music—the unadulterated passion and joy for this music.

Kevin: Let’s talk about your equipment. How did it evolve over time?

Jimmy: I started with a Conn horn and mouthpiece. During college, I switched to a King 3B with a Bach 12C mouthpiece. And that was my setup of choice all the way into the late ’80s, early ’90s.

It became more of a struggle to feel like you were really filling that horn with enough air to be heard—in the midst of the guitars, bass, electric keyboards, vocals—all coming out of a PA . . . on 12! So whether you liked it or not, you ended up blowing triple forte the entire night because we didn’t have a volume knob—all we had were lips and lungs. So I moved up to a Bach 6 1/2 AL mouthpiece, which has a deeper cup. That allowed more air flow into the King and gave me more power.

Well, the mouthpiece evolution continued to the Schilke 50; it’s a big mouthpiece. It’s got a very deep cup and a relatively thin rim compared to other mouthpieces that size. You can give the horn everything you got because the mouthpiece allows a much bigger air flow.

Kevin: What about horns?

Jimmy: I played a Silver King 3B for a lot of my career. I switched from my 3B to the Yamaha YSL-691. Yamaha approached us and asked if we’d like to try their horns. I subsequently play the Yamaha 691, that’s a .508 bore and an 8″ yellow brass bell. It has a nickel-silver slide and three interchangeable leadpipes.

Kevin: Did you play bass trombone on a few of the Chicago albums?

Jimmy: Yes, actually. I first played bass bone in the orchestra at Quincy College. It’s a double-trigger King with a sterling silver bell. With Chicago, when I had to go downstairs, I did, in fact, bring that horn up to Caribou Ranch, because we would double and triple track. Each time we did another generation, we would voice switch. And then, add alternate voices, because we’d be dealing with more complex chord structure. We’d be doing raised 9th’s or flatted 5th’s. And in the last generation, I’d jump to the bass bone and do the pedals.

Kevin: So the bass trombone was always the last pass?

Jimmy: Yes, the pedals were always the last pass. Because, oftentimes, I would play alternate pedals on the bottom depending upon the nature of the chordal structure. It wasn’t always obvious where to go on the bottom until we did the double and I could hear the voicings.

Kevin: Did you do much work outside of Chicago?

Jimmy: Well, I did as much as time allowed. My career has been so all consuming. Like I told you, in the beginning, we were on the road three hundred days a year. Way back in the beginning, I played with Three Dog Night. I played with a group called the Knack, which were out of Chicago. I also played a bunch of stuff with Elton John.

Kevin: What about the Toto session with Jerry Hey?

Jimmy: Yes, the Toto session. Steve Lukather and David Paich said, “We want the grease! We want this to be ‘Pankowized!’ ” The horn section was Jerry Hey, Gary Grant, Jerry Horne, Tom Scott, Gary Herbig and a really great trombone player named Bill Reichenbach! I mean, it doesn’t get much better than that and it was a thrill for me to be in that section.

Kevin: Do you recall the name of the Toto album you recorded?

Jimmy: No, but it was “Rosanna” and “Pamela.” [Jimmy singing.] I don’t remember the title of the album but it was their biggest one. It won a Grammy and Rosanna was Song of the Year. It was great to be on that record. [The album Toto IV won a Grammy in 1982 with “Rosanna” from that album winning Song of the Year.]

Kevin: I’ve heard you recorded with Dick Nash.

Jimmy: Dick Nash! Dick Nash! I was fortunate enough, this was back in the early days, to do a movie date with Dick in L.A. Now, I was scared because I wasn’t one of the cats. I wasn’t a first-call guy. I wasn’t a tenth-call guy! So I get this call and show up to Paramount. Kevin, I was scared shitless. I was thinking, “What in the hell am I doing here?” And this section is Dick Nash, Carl Fontana, and Dick “Slide” Hyde! I mean, here’s all these legends, these monsters! So Dick Nash leans over towards me and says, “Hey, kid. Welcome to the bigs. It’s great to meet you.” He was nothing but encouraging and he put me at ease. And man, to sit in that section and to hear these guys was, it was life changing. These guys, I mean, perfect execution. Literally, perfect everything. And I asked them a thousand questions. I’m telling you, it was like sitting next to the Dali Lama. I will never forget how nice Dick Nash was and what an impression he made upon me. Please tell him that his kindness and his words of wisdom were a life-changing moment for me.

Kevin: I certainly will. Do you recall the name of the movie?

Jimmy: I believe it was the soundtrack for Jimmy Guercio’s movie, “Electra Glide Blue.”

Kevin: Here are a few rapid fire questions. What do you believe to be your finest composition that has been recorded by Chicago?

Jimmy: The Ballet for a Girl in Buchannon off of Chicago II. [This album is also known as Chicago.] And I’ll tell you, I minored in piano at DePaul and it really helped me with composition.

Kevin: What are your favorite Chicago albums?

Jimmy: I think our first album, Chicago Transit Authority, because it was our pioneer album and it set the mold. Also, Chicago II because it was the full template of everything that is Chicago, musically.

Kevin: What album do you think best captured the ensemble sound of Chicago?

Jimmy: The digitally remastered album Live in Japan. It was recorded in Osaka, Japan, in 1972. Also, the digital remaster of Chicago II sounds great.

Kevin: What album or track do you think captured the Chicago horn section sound?

Jimmy: A piece from Chicago III called “Elegy.” In particular, the movement called “Canon.”

Kevin: What are a few examples of your own playing with Chicago that you like the best?

Jimmy: “Night and Day” and “Chicago” from the Night and Day Chicago Big Band album. “Beginnings” from Chicago Transit Authority and “Mother” from Chicago III.

Kevin: What is your favorite Chicago tune that you perform live?

Jimmy: I’ve always been partial to “Beginnings.”

Kevin: In conclusion, do you have any advice for young trombonists?

Jimmy: Yes.

#1. Hard work. Practice harder than anyone else. You must develop self-discipline—not teacher-discipline—self-discipline.

#2. Be passionate. Nothing done well is done without passion. People who are the most successful are the most passionate. If you don’t love it, do something else.

#3. Have fun and enjoy the ride. Everything’s better if you’re enjoying it.

Kevin: I want to thank you for making the time to talk with me. It’s been an absolute pleasure and an opportunity that I will never forget. On behalf of thousands of musicians and fans world-wide, I would like to congratulate you for all of your accomplishments and on being the recipient of the International Trombone Assiocation’s 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award. Congratulations, Jimmy—no one deserves it more than you!

More information about James Pankow can be found in the January 2004 issue of the ITA Journal, volume 32, number 1.

You can read the original article cover HERE.

Kevin M. McManus is a musician and educator in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He teaches first–fourth grade general music at Pivik Elementary in the Plum Borough School District. Kevin is also on the faculty of Seton Hill University and Westminster College.

© Copyright 2025 Chicago Live Events, Inc. All Rights Reserved.